What is the future of virtual and augmented reality?

Explore the future of virtual reality, from college campus tours with a DIY VR headset to a space suit that will help astronauts prepare for a Mars landing.

Patrick Sisson

November 8, 2022 • 6 min read

Both consumer demand and new product launches are driving the shift for incorporating virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) technology in everyday life.

College tours, space training, and immersive storytelling are all now taking advantage of VR technology.

The VR space is the next frontier for techno-pioneers.

Technological shifts don’t always begin with keynote speeches or media frenzies. Sometimes, they just arrive in the mail.

High school students and aspiring designers accepted to the Savannah College of Art and Design (SCAD) received more than just a letter in 2015; they received a white cardboard mailer that when opened, unfolded, and reassembled turned into a set of goggles—a device known as Google Cardboard, the tech giant’s low-cost way to introduce the masses to virtual reality (VR). Prospects could load a virtual-tour website on their smartphone; slip the phone into the cardboard glasses; and with this makeshift headset, take a virtual walk around one of SCAD’s four campuses.

According to YouVisit (the tech company that created the SCAD tour), potential students spent an average of 10 minutes on the virtual campus, and some even toured for nearly an hour. YouVisit’s turn toward VR with SCAD is a vision of the future of the company, which launched in 2009 to provide online college tours and now represents the promise of widespread VR adoption, currently working with more than 1,000 educational institutions, as well as travel and leisure, hospitality, and real estate firms.

While big names like Oculus Rift and Microsoft HoloLens have captured widespread attention, numerous smaller firms, developers, and practitioners—who are already immersed in the technology and actively designing the future of virtual reality—say it’s about to catch up with science fiction. The remaining technical hurdles certainly haven’t stopped the money from flowing. The market for virtual and augmented reality is expected to grow by $162 billion by 2025, driven by both consumer demand and new product launches.

Like SCAD, many investors see beyond the opportunities in front of their faces.

“These [interactive college] tours are just the beginning,” says David Hanak, the school’s executive director of interactive media. “It’s a great promotional tool, but there is so much more to this technology. We want to bridge the gap between the on-ground and online experience. There’s a big issue with e-learners not being engaged in the classroom, and this can change that.”

VR simulations for astronaut training

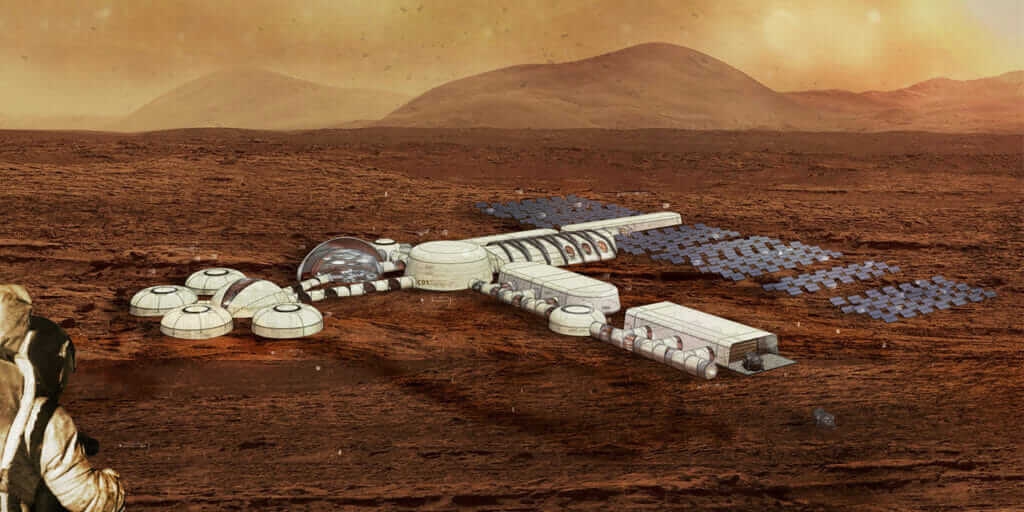

Like many things sci-fi, it’s good to start with outer space when explaining the current state of VR technology. Pablo de León, an Argentine aerospace engineer teaching at the University of North Dakota, is working on a VR space suit—the NDX-2—for NASA to help run astronauts through simulations for a potential Mars landing.

Sure, de León says, any traveler to Mars will welcome a way to simulate home. But more important, there’s no way NASA can understand what a year in space will be like without actually launching a mission. This fully pressurized suit with an Oculus Rift headset may help technicians troubleshoot before actually launching a human on a one-way trip to the red planet.

NASA has a long history of utilizing VR as a means to train crew members, but usually these programs’ graphics aren’t fully realistic due to issues of computer lag time.

According to de León, despite great leaps forward with processing speeds, technical limitations mean actual movement and that displayed in a virtual environment still don’t perfectly match up. As de León explains, “motion sickness inside a spacesuit is always a bad idea.” So while the NDX-1 has stood up to harsh environmental tests in places such as Antarctica, the VR tech isn’t fully responsive.

“I’m a space-suit guy, and I’m confident we’ll be able to reduce the lag time,” he says. “But whenever you’re developing a VR system, as soon as you increase the complexity of the graphics, you have that problem.”

De León and his team want to develop technology that shows what a certain space feels like, as opposed to just looks like. That idea, from photographer and designer Josh Pabst’s article about the potential and promise of VR in architecture, points to the true hurdle for VR designers: developing a system with enough memory and processing power to overcome disruptive lag time.

“The truth is, we’re not going to be able to do a real-time, 360-degree animation anytime soon,” Pabst says. “But in order for the experience to be great, it doesn’t have to be photo-real; it just needs to be fluid. Computers aren’t fast enough, but the technology is catching up. I think there’s almost no doubt the gaming industry and video games will get there first. The headset is there. Developing content is the new hurdle.”

VR redefining storytelling

Robert Hernandez, a media theorist, practitioner, and journalism professor at USC, has been thinking about what the media landscape will look like when we finally take that technological leap. He’s spent years looking at how new mediums alter our concept of storytelling; back in 2006, he created a panoramic, immersive VR site that allowed users to experience the emptiness of the Bering Sea. He sees the technological leap as inevitable, but asks how—amid an expected onrush of advertising and marketing plays in VR—the new medium will redefine media?

“Google Glass has made it so much more real for people to see a virtual or augmented reality world, and Oculus Rift is taking it further,” he says. “They have great technology, but not the storytelling skills.”

Hernandez points to the work of Nonny de la Peña—known as the “godmother of virtual reality”—as an example of what the medium can accomplish. She has shown a more immersive, experiential future for the technology, instead of merely giving someone a new way to view the same landscape.

To help communicate issues of hunger, de la Peña built a VR experience that lets a user understand what it was like to wait in line for your next meal. Her work suggests that amid all the hype over transformative media environments and tourist experiences, the sea change that VR could usher in may, in part, be about a more humane form of storytelling.

“Think of the beginning of radio,” Hernandez says. “For years, we just had people reading the newspaper into the microphone before it truly developed. There’s a learning curve that’s happening with virtual reality right now. Storytellers need to get into this space.”

This article has been updated. It originally published June 2015.

About the author

Patrick Sisson

Patrick Sisson is a Los Angeles–based design and culture writer who has made Stefan Sagmeister late for a date and was scolded by Gil Scott-Heron for asking too many questions. His work has appeared in Dwell, Pitchfork, Motherboard, Wax Poetics, Stop Smiling and Chicago Magazine.