Just say whoa: GlaxoSmithKline and the future of 3D-printed pharmaceuticals

Learn how pharmaceutical giant GlaxoSmithKline is using technology to foster a culture of innovation, 3D-printed pharmaceuticals, and more.

By revenue, the global pharmaceutical market ranks higher than many countries. With more than $1 trillion in receipts, the combined earnings of an industry that includes major players such as Pfizer, Roche, and GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) is equivalent to a quarter of the annual U.S. federal government spend.

The stakes in this market are high, and the path leading to the commercialization of a new drug discovery is long and full of expensive pitfalls: The cost can be more than $1 billion per commercial product launch.

“At an industry level, we are at 90 to 95 percent attrition,” says Martin Wallace, GSK’s director of technology seeking, on the success rate of bringing new products to market. Wallace joined GSK four years ago, and his work includes looking at how emerging technology—like 3D-printed pharmaceuticals—can help improve R&D productivity and deliver new benefits to patients.

One opportunity in the pharmaceutical industry is the use of 3D printing to make tissue samples. “We’re trying to create tissues or organs that are representative of a human,” Wallace says, noting that success in this area would reduce the need for animal testing and lead to a clearer understanding of drug performance. “Anything we can do to help with that translation of early-stage data and what is representative of how a drug is likely to behave in a human is critical.”

The future of medicine

3D printing has the potential to offer many other benefits to GSK patients. “One of the areas we are exploring is whether we can print patient-specific dosage forms,” Wallace says. “While the future vision posited by many includes printers in pharmacies and homes, we believe there are a lot more challenges to be overcome before this becomes a reality. Nonetheless, our innovation model compels us to experiment.

“Because personalized medicine has the ability to stratify patient populations and segregate them in a more precise manner, it means that we can provide more specific solutions for that patient,” he continues. “Printing tailored medicine could simplify our supply chain dramatically.”

To this end, GSK is investigating the advantages 3D printing pharmaceuticals could bring to the manufacture of pills and tablets. A drug comprises the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) and the excipient, or the inert substance used as a carrier for the API. The challenge is to convert the API into a “curable ink” or other 3D-printable material, Wallace says.

Inkjet 3D-printing methods are of particular interest to the pharmaceutical industry because they have many parallels with current manufacturing processes, and may offer a more efficient longer-term printing solution. However, 3D printing will not replace today’s production methods for some time. “Current technology allows us to produce up to 1.6 million tablets per hour,” Wallace says. “You’re going to need a lot of printers to achieve that sort of production.”

In addition to tailoring medicine to patients, 3D printing as a manufacturing technique for the pharmaceutical industry has several other advantages. Wallace points to the first 3D-printed drug approved by the Federal Drug Administration (FDA): Spritam, an epilepsy medicine manufactured by Aprecia Pharmaceuticals. “What they are trying to achieve is an almost instantaneous release of the drug, with a very high drug loading, which is difficult using conventional technology,” he says.

Accelerating innovation by 3D printing pharmaceuticals

3D printing also unlocks the ability “to create complex shapes and geometry in order to deliver the drug in a different way,” Wallace says. Manipulating the geometry of a tablet could be used to adjust the drug loading, modify the release, or mask the taste of a medicine.

Furthermore, the FDA has also performed a deep dive into 3D printing to manufacture medicine. The regulator is keen to encourage 3D printing drugs and believes it will “stimulate continual innovation in pharmaceutical manufacturing technology.”

Wallace agrees and reflects back on his student days as a mechanical engineer, when traditional testing and analysis took an inordinate amount of time—something that technology such as 3D printing can help alleviate. “With rapid prototyping, you could have 15 different iterations in the same time,” he says. “You accelerate the rate of learning at a lower cost.”

Accessing an untapped resource

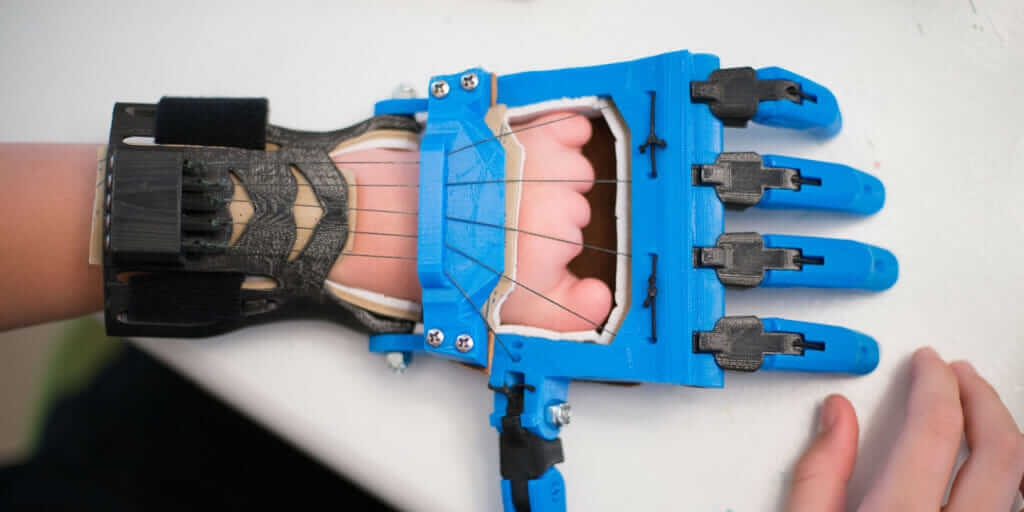

Even in areas away from the frontiers of science, Wallace believes that 3D printing is a powerful tool. Specifically, 3D printing can give access to an organization’s often-untapped resource: the creativity of its people. A 3D model can serve as a common platform to communicate ideas; something that can prove difficult between different disciplines using words alone. “We’re an organization of around a 100,000 people, and we’re all patients or may be patients in the future,” he says.

Earlier this year, with help from the Autodesk Fusion 360 Street Team, GSK launched a 3D-printing competition for employees to submit ideas—designed in Fusion 360—that would have an impact on the business. “Competition entries came from customer-facing people to right into the belly of research and development,” Wallace says. “3D printing gave these groups the ability to take ideas and communicate them in a way that is understandable to a wider population.

“We started to see ideas that we’d never considered and applications where 3D printing could be of benefit,” he continues. Ideas for the application of 3D printing in pharmaceuticals included product-packaging modifications that would ease use for older people, among others.

These kinds of examples show that, although 3D-printed pharmaceuticals and mass customization of medicine are still some distance away, 3D printing’s ability to accelerate innovation is its real value in pharma today.

About the author

Michael Petch

Michael Petch is the author of several books on 3D-printing technology and a regular speaker at international conferences.