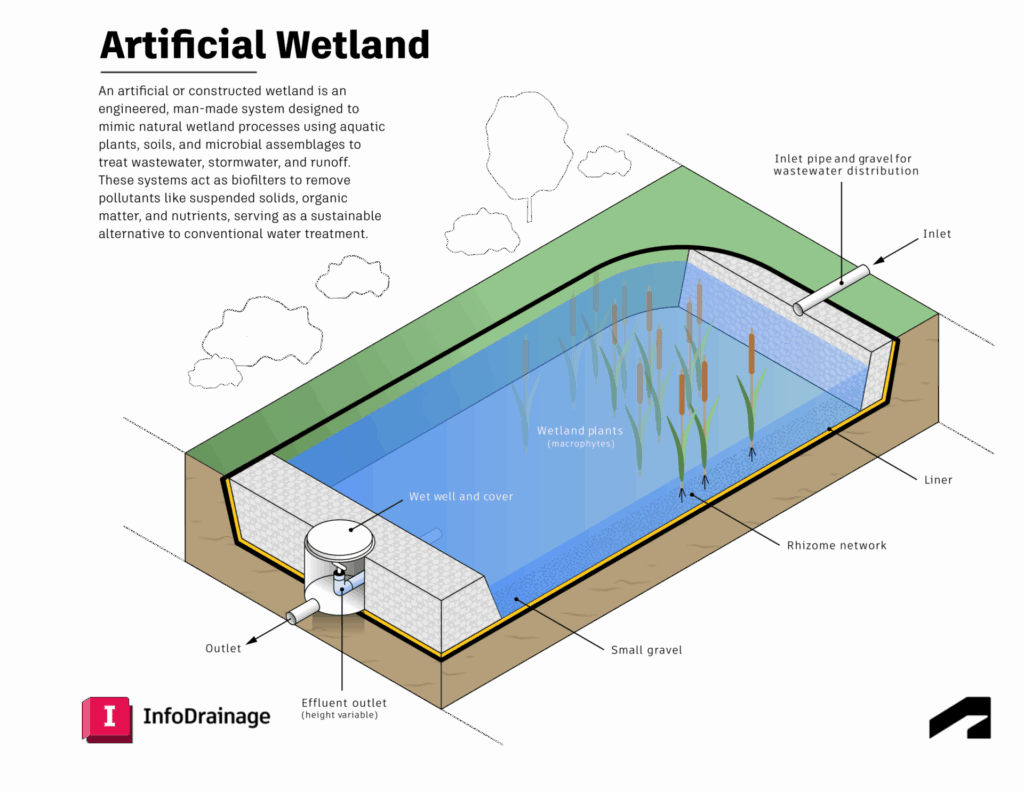

An artificial wetland is a constructed ecosystem designed to manage water and pollution through engineered processes that are designed to mimic natural processes using plants, soils, and microbes to treat wastewater or storm runoff.

As a type of treatment wetlands, artificial wetland systems serve as a comprehensive ecological infrastructure for water quality improvement, supporting environmental protection and habitat restoration. These wetlands are purposefully built in upland areas for pollution control – places which do not have a prior history of being a wetland – and their success depends on being engineered as hydraulic assets rather than residual landscape features.

Site-specific design with InfoDrainage

Also often called constructed wetlands, these sustainable drainage assets are specifically designed to treat water by mimicking the natural functions of wetlands – such as pollutant removal, waste breakdown, and habitat creation – using vegetation, soil, and microorganisms.

For civil engineers and drainage designers, their value lies not in aesthetics, although they can also be quite beautiful sometimes, but in performance: artificial wetlands provide storage, regulate discharge, and improve runoff quality while reducing reliance on energy-intensive, mechanical infrastructure.

Importantly, constructed wetlands can be used to treat both domestic and industrial wastewater, as well as manage stormwater runoff in urban areas. The selection of plant species, such as cattails, bulrushes, and other emergent macrophytes, plays a crucial role in these systems, as their roots and stems help filter out contaminants and provide habitat for beneficial microbes.

When designed properly, a wetland functions as a defined hydraulic unit within the drainage network, not a passive landscaped area. Digital design tools such as InfoDrainage make this achievable by allowing wetlands to be modelled accurately, thoroughly stress-tested, and optimised against future degradation as part of an integrated, site-specific drainage solution. This can be done well before installation.

Artificial wetlands from an engineering perspective

In drainage terms, a constructed wetland is best understood as a shallow storage feature with controlled outflow and extended residence time. Its primary engineering functions are:

- Flow attenuation: temporary storage reduces peak discharge rates

- Volume management: extended detention and, where appropriate, infiltration or reuse

- Water quality treatment: removal of sediments and pollutants through physical and biological processes

- System resilience: gravity-led operation with minimal mechanical dependency

Maintaining adequate treatment capacity is essential to ensure reliable performance, as overloading can reduce the effectiveness of pollutant removal. Unlike piped systems designed for rapid conveyance, wetlands are designed to slow water movement, increasing contact time and enabling treatment. Hydraulic control, geometry, and integration with upstream sustainable drainage (SuDS) components therefore directly determine performance.

There are two main categories of artificial wetlands: Surface flow and subsurface flow.

Surface flow wetlands

Surface flow systems, also known as surface flow wetlands or free water surface wetlands, convey runoff slowly above ground through emergent vegetation.

They have a few clear engineering characteristics:

- Straightforward earthworks and construction

- Clear visibility for inspection and maintenance

- Strong sediment settlement and initial pollutant removal

- Typically a larger land use than subsurface systems

- Surface flow constructed wetlands always have horizontal flow of wastewater across the roots of the plants, rather than vertical flow.

Typical applications for these types of systems include downstream attenuation and polishing features receiving flows from upstream source control (eg, permeable paving, swales, detention basins).

Subsurface flow wetlands

In subsurface flow systems, water flows horizontally or vertically through engineered media beneath the surface. Subsurface flow systems can be designed as horizontal subsurface flow or vertical flow systems, although vertical flows are considered to be more efficient with less area required compared to horizontal flows.

They have their own characteristics:

- Reduced footprint compared to surface systems

- No exposed standing water

- Higher treatment efficiency per unit area

- Typically require less land area for water treatment

- Greater sensitivity to media selection and long-term clogging risk

Typical applications for this type include space-constrained sites or locations where public safety, odour, or visual constraints limit surface water features.

Treatment processes that engineers can design

Constructed wetlands rely on treatment mechanisms that are closely tied to hydraulics:

- Sedimentation: reduced velocities allow suspended solids to settle

- Filtration: vegetation and media physically trap particles

- Adsorption: metals, phosphorus, and hydrocarbons bind to soils and substrates

- Biological transformation: microbial communities reduce BOD (Biochemical Oxygen Demand) and convert nitrogen through nitrification and denitrification

- Removing contaminants: constructed wetlands are effective at removing many pollutants, including organic matter, heavy metals, and other pollutants, through a combination of physical, chemical, and biological processes

Constructed wetlands are usually designed to remove water pollutants such as suspended solids, organic matter, and especially nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus. The community of microorganisms in constructed wetlands, known as periphyton, is responsible for approximately 90 percent of pollutant removal and waste breakdown.

From a design standpoint, performance depends on residence time, even flow distribution, and effective use of available volume. It’s important to stress that these parameters must be deliberately engineered rather than assumed.

Pathogen removal in artificial wetlands

One of the key benefits of constructed wetlands, especially subsurface flow constructed wetlands, is their ability to remove pathogens from wastewater and stormwater runoff. In these systems, water flows horizontally or vertically through a bed of soil and wetland plants, such as common reed and cattails, which act as natural filters. The dense root networks and the microbial activity within the wetland soils create an environment where harmful microorganisms are trapped, broken down, or outcompeted by beneficial microbes.

This combination of physical filtration, antimicrobial properties of certain wetland plants, and active microbial processes makes subsurface flow artificial wetlands highly effective at pathogen removal. As a result, these engineered wetlands play a vital role in improving water quality and protecting public health, particularly in applications involving domestic wastewater or urban runoff.

Designing artificial wetlands with InfoDrainage

Wetlands as modelled assets

InfoDrainage allows wetlands to be represented as defined storage features within the drainage network. This enables sizing based on:

- Contributing catchment areas

- Runoff rates and routing

- Design storms and climate change allowances

- Allowable discharge rates and downstream constraints

Accurately modeling effluent flows through the artificial wetland system is essential to ensure proper treatment and optimize wetland performance. This approach avoids excessive land take driven by conservative assumptions and supports proportionate, site-specific design.

Flow control and hydraulic performance

Designing effective wetlands depends on predictable inflow, controlled water levels, and managed discharge. With InfoDrainage, engineers can iterate:

- Outlet structures (orifices, weirs, staged controls)

- Normal operating levels and flood levels

- Emergency overflows and exceedance routing

This makes it possible to demonstrate compliance with flow-rate targets while maintaining treatment effectiveness during frequent and extreme events. In treatment wetlands, maintaining optimal hydraulic and environmental conditions is crucial to ensure effective pollutant removal and overall system performance.

Integration across the SuDS treatment train

Constructed wetlands typically perform best as part of a wider SuDS strategy. As integrated treatment systems, constructed wetlands work alongside other SuDS components to enhance water purification and pollution removal.

It is common and encouraged to “daisy-chain” sustainable drainage components together and measure their effectiveness, which InfoDrainage excels at, providing seamless integration with sustainable features like:

- Swales: Vegetated channels that slow runoff and provide pretreatment

- Porous pavement: Man-made surfaces that allow rainwater to infiltrate directly where it falls

- Infiltration trenches: Rock-filled excavations that promote percolation into surrounding soils

- Cellular storage systems: Underground tanks that hold and release stormwater gradually

- Soakaways: Pits or trenches that hold water that are often filled with plastic crates.

- Bioretention systems: Sometimes called bioswales or bioretention cells (and sometimes rain gardens, although they are semantically different)

- Rain garden: A stormwater management design that uses natural materials and processes to collect and filter runoff from impermeable surfaces such as streets, driveways, and sidewalks.

- Wet ponds and infiltration basins are treated essentially the same as artificial wetlands inside InfoDrainage; the differences are mostly in the design details.

By modelling the full system, engineers can distribute storage and treatment across the site, improving resilience and reducing pressure on any single component.

Key design considerations for engineers

Hydraulic layout and geometry

Experimentation is encouraged to avoid poor performance, which is often caused by preferential flow paths or hydraulic bypassing within the wetland system, where water moves too directly from inlet to outlet without adequate contact time.

Design responses within the wetland system include:

- Appropriate length-to-width ratios

- Distributed inlets rather than single-point inflow

- Internal berms, islands, or level changes to promote even flow distribution

One clear advantage of using InfoDrainage to design these systems is that it helps verify that storage volumes in the wetland system are being used as intended during design events.

Ground conditions and lining strategies

Early design decisions are required on whether the wetland will infiltrate into the ground or be lined to provide predictable attenuation and treatment. Ground investigation data should inform liner selection, groundwater protection, and compliance with local policy.

Lining is especially important for specific types of installations. For example, constructed wetlands can be designed to treat drainage from mining activity, helping to control pollution from sources such as acid mine drainage and protect groundwater quality.

Sediment management and maintainability

Just as with all SuDS, these are not “set it and forget it” assets. In particular, stormwater wetlands are vulnerable to sediment loading. In addition to soil erosion and runoff, animal wastes can contribute to organic inputs and sediment loading in constructed wetlands.

Key measures for maintenance include:

- Upstream forebays or silt traps

- Defined access routes for desilting

- Protection of planted zones from excessive burial

Maintenance assumptions should be documented as part of the drainage strategy – and not left to later stages.

Vegetation from a functional perspective

While planting design is often led by landscape teams, engineers must ensure vegetation assumptions align with hydraulic intent:

- Selection of different species of wetland plants is important, as various species have distinct rates of pollutant uptake and can optimize removal efficiency

- Choose species that are tolerant of fluctuating water levels

- Make zonation choices that preserves effective storage

- Avoidance of dense planting that could restrict flow paths over time

Constructed wetlands can also attract a variety of bird species, which enhances biodiversity. In fact, the presence of birds generally serves as an indicator of a healthy wetland ecosystem.

Climate and seasonal performance

Biological treatment efficiency varies seasonally. Engineers should:

- Check winter performance assumptions

- Design for climate change rainfall events

- Confirm exceedance routing under blocked or overwhelmed conditions

InfoDrainage enables these scenarios to be tested without redesigning the system, with the ability to apply regional and custom rainfall standards.

Constructed wetlands are particularly suitable for use in developing countries due to their low cost and adaptability to local conditions, making them an effective solution for climate adaptation in resource-limited settings.

Where constructed wetlands add the most value

Artificial wetlands are particularly effective where multiple constraints overlap:

- Residential developments: combining attenuation, treatment, and amenity

- Commercial and industrial sites: polishing runoff from large impermeable areas, and treating municipal wastewater and industrial wastewater as part of integrated wastewater treatment solutions

- Urban regeneration: replacing underground storage with visible blue-green infrastructure where space allows, and enabling the reuse of treated water as irrigation water for landscaping and agriculture

- Infrastructure schemes: managing highway runoff while delivering environmental enhancement and supporting a broad range of applications, including the treatment of raw sewage, storm water, agricultural, and industrial effluent

The biggest benefits of artificial wetlands

Add it all up, and you get a list of clear benefits of installing artificial wetlands:

- They are versatile and cost-effective, offering lower construction and operating costs compared to conventional wastewater treatment systems.

- They can be integrated into urban planning and development to enhance sustainability and resilience against urbanization impacts.

- They help mitigate flooding by managing stormwater runoff.

- They reduce the heat island effect in urban settings through cooling by evapotranspiration.

- They assist with carbon sequestration through photosynthesis and the accumulation of organic matter in anaerobic soil conditions.

- The aesthetic value of artificial wetlands visibly makes urban environments more pleasant and communities better places to live.

Conclusion

Constructed wetlands are a legitimate and robust drainage solution when designed with the same rigour applied to pipes, tanks, and basins. They require clear hydraulic intent, controlled outlets, managed flow paths, and defined maintenance strategies.

InfoDrainage enables civil engineers to design wetlands with confidence, testing performance, integrating them into the wider SuDS network, and clearly demonstrating compliance with flow control and resilience requirements.

When treated as engineered infrastructure rather than decorative features, artificial wetlands provide a practical, sustainable, and defensible approach to modern drainage design.

Go deeper into sustainable drainage design

- Read the SuDS manual: We have a comprehensive Guide to Representing SuDS in InfoDrainage in accordance with the SuDS Manual Ciria 753.

- Features and functionality: Our documentation can help you accurately model and size rain gardens, as well as all of the Stormwater Controls available inside InfoDrainage.

- Learn the basics: We offer an excellent video, “Fundamentals of Drainage Design,” for budding civil engineers, urban planners, or anyone interested in understanding how drainage systems work.

- Try it out: Don’t have a copy of InfoDrainage? We offer a 30-day free trial with no credit card required.

- Get it for free? Are you a student or educator? If so, we have some very good news for you.