This post is also available in: Français (French) Italiano (Italian) Deutsch (German)

Learn what piezoelectricity is, see the piezoelectric effect in action, explore piezoelectric crystals and piezo power applications, and discover why piezoelectric power is poised for energy-harvesting breakthroughs.

Elevate your design and manufacturing processes with Autodesk Fusion

How the piezoelectric effect turns crystals into power

Piezo what? Piezoelectricity sounds like a lot to take in, but it’s simple to understand. The word piezoelectric originates from the Greek word piezein, which literally means to squeeze or press. Instead of squeezing grapes to make wine, we’re squeezing crystals to make an electric current! Piezoelectricity is in a ton of everyday electronic devices, from quartz watches to speakers and microphones.

What is piezoelectricity?

Piezoelectricity is a phenomenon in which certain crystalline materials generate an electrical charge in response to applied mechanical stress. Conversely, the same materials deform when exposed to an electric field. This reversible effect—converting mechanical energy into electrical energy and vice versa—makes piezoelectricity useful in a wide range of modern technologies, from sensors and actuators to ultrasound equipment and everyday devices like lighters.

The discovery of piezoelectricity dates back to 1880, when French physicists Jacques and Pierre Curie first observed the effect in quartz crystals. The term itself comes from the Greek word piezein, meaning “to press” or “to squeeze,” directly reflecting the role of applied pressure in generating electrical charge.

To understand why only some crystals are piezoelectric, it helps to look at their atomic structure. All crystals are made of repeating arrangements of atoms called unit cells. In most crystals, such as iron, this unit cell is symmetrical—so when pressure is applied, the internal charges cancel out, preventing any net electrical effect. Piezoelectric crystals, however, are asymmetrical. Although normally balanced and electrically neutral, their lack of symmetry allows charges to shift when stressed, producing a measurable voltage.

This same asymmetrical structure also underlies the reverse piezoelectric effect: when an electric field is applied, the crystal physically expands and contracts. This property has been harnessed in technologies such as inkjet printers, ultrasonic cleaners, and precision actuators.

Practical applications of piezoelectricity range from the everyday to the cutting edge. In the common cigarette lighter, a quick mechanical strike on a piezoelectric crystal generates a high-voltage spark. In medicine, ultrasound imaging depends on piezoelectric transducers. Looking forward, researchers and inventors are exploring piezoelectricity for energy harvesting—capturing the mechanical energy of footsteps, vibrations, or other everyday motions to generate clean power for low-energy devices.

Types of piezoelectric materials

Piezoelectric materials can be broadly divided into natural and synthetic (man‑made) categories. The key feature that makes a material piezoelectric is the lack of a center of symmetry in its crystalline structure. This asymmetry allows electric charges to be displaced under stress, generating voltage, and conversely, permits mechanical movement when exposed to an electric field.

Natural piezoelectric materials

The first and most iconic piezoelectric material used in practical devices was quartz, discovered and studied by Jacques and Pierre Curie in 1880. Quartz remains critical in oscillators and resonators due to its stability and reliability. However, many other natural substances also exhibit piezoelectric effects:

- Rochelle salt – one of the earliest natural piezoelectric crystals studied in laboratories.

- Tourmaline and topaz – naturally occurring minerals with strong piezoelectric responses.

- Cane sugar and silk – examples of organic crystals with piezoelectric properties.

- Bone and wood – biological materials that display piezoelectricity because of their anisotropic (direction-dependent) molecular structures.

While natural crystals helped establish the foundation of piezoelectric science, their performance, consistency, and mechanical strength are often limited compared to engineered materials.

Synthetic piezoelectric materials

As piezoelectric technology advanced—particularly after World War I—researchers began developing artificial materials to improve upon the durability and performance of natural crystals. Some of the most important synthetic materials include:

- Barium Titanate (BaTiO₃): Discovered during World War II, this was one of the first widely used ceramic piezoelectrics. It is durable and offers strong electromechanical properties compared to quartz.

- Lead Zirconate Titanate (PZT): Perhaps the most widely used piezoelectric material today, PZT can generate higher voltages than quartz under the same mechanical stress, making it ideal for sensors, actuators, and transducers.

- Lithium Niobate (LiNbO₃): A high‑performance ceramic combining lithium, niobium, and oxygen, similar in behavior to barium titanate but with favorable optical properties, making it useful in photonics and telecommunications.

- Polyvinylidene Fluoride (PVDF): A piezoelectric polymer with flexibility, light weight, and adaptability, making it suitable for applications where ceramics are too brittle, such as wearable sensors and medical devices.

Natural vs. synthetic: Key differences

- Structure: Natural crystals form through geological or biological processes, with limited variation in their atomic lattices. Synthetic materials can be engineered to fine‑tune their properties.

- Performance: Synthetic ceramics like PZT typically produce larger voltages and withstand greater mechanical stress.

- Applications: Natural piezoelectrics (especially quartz) remain important in precision devices such as watches and oscillators, while engineered ceramics and polymers dominate in high‑performance electronics, medical systems, and energy harvesting.

Piezoelectric effect: Direct and inverse

The piezoelectric effect describes the two-way interaction between mechanical stress and electric charge in non-centrosymmetric crystalline materials. It occurs in two complementary forms: the direct effect and the inverse effect.

1. Direct Piezoelectric Effect (Mechanical → Electrical):

When a mechanical stress (T) is applied to a piezoelectric material, the asymmetric arrangement of charges in the crystal lattice shifts, creating a net surface charge. This results in a measurable surface charge density (δ) that can be collected as electrical output. The relation is expressed mathematically as:δ=d⋅Tδ=d⋅T

where:

- δδ = electric displacement or surface charge density (C/m²)

- dd = piezoelectric strain constant (C/N or m/V), a material-dependent coefficient

- TT = applied mechanical stress (N/m²)

This direct effect underlies the working principle of piezoelectric sensors, microphones, and energy-harvesting devices, where applied vibrations or pressure translate into electrical signals.

2. Inverse Piezoelectric Effect (Electrical → Mechanical):

Conversely, when an external electric field (E) is applied to a piezoelectric material, the lattice deforms, producing strain (S) in the material. This is known as the inverse piezoelectric effect, described by:S=d⋅ES=d⋅E

where:

- SS = mechanical strain (ΔL / L)

- dd = piezoelectric strain constant (m/V)

- EE = applied electric field (V/m)

This reversible effect is the basis for piezoelectric actuators, ultrasonic transducers, and precision positioning systems, where applying a voltage leads to controlled mechanical displacement.

How piezoelectricity works

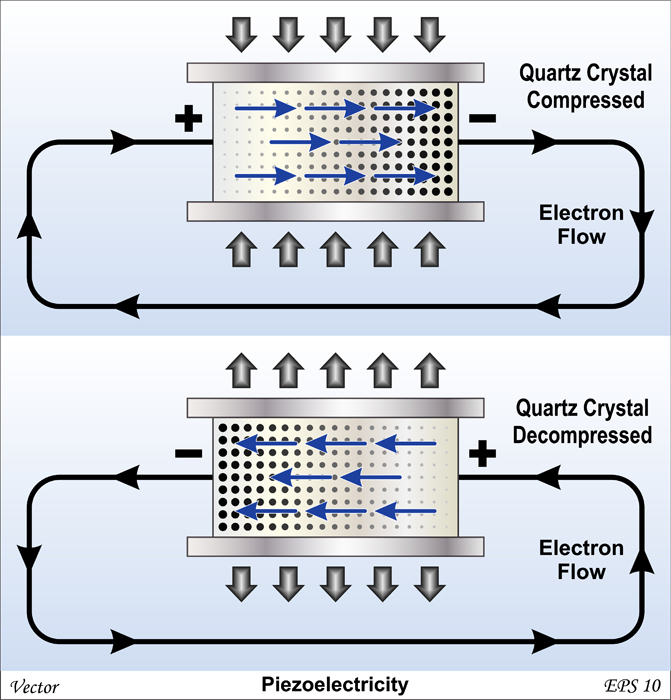

We have specific materials suited for piezoelectricity applications, but how exactly does the process work? With the Piezoelectric Effect. The most unique trait of this effect is that it works two ways. You can apply mechanical or electrical energy to the same piezoelectric material and get the opposite result.

Applying mechanical energy to a crystal is a direct piezoelectric effect and works like this:

- A piezoelectric crystal is placed between two metal plates. At this point, the material is in perfect balance and does not conduct an electric current.

- Mechanical pressure is then applied to the material by the metal plates, which forces the electric charges within the crystal out of balance. Excess negative and positive charges appear on opposite sides of the crystal face.

- The metal plate collects these charges, which can be used to produce a voltage and send an electrical current through a circuit.

That’s it, a simple application of mechanical pressure, the squeezing of a crystal, and suddenly you have an electric current. You can also do the opposite, applying an electrical signal to a material as an inverse piezoelectric effect. It works like this:

- In the same situation as the example above, we have a piezoelectric crystal between two metal plates. The crystal’s structure is in perfect balance.

- Electrical energy is then applied to the crystal, which shrinks and expands the crystal’s structure.

- As the crystal’s structure expands and contracts, it converts the received electrical energy and releases mechanical energy in the form of a sound wave.

The inverse piezoelectric effect is used in a variety of applications. Take a speaker, for example, which applies a voltage to a piezoelectric ceramic, causing the material to vibrate the air as sound waves.

The discovery of piezoelectricity

Piezoelectricity was first discovered in 1880 by two brothers and French scientists, Jacques and Pierre Curie. While experimenting with various crystals, they discovered that applying mechanical pressure to specific crystals like quartz released an electrical charge. They called this the piezoelectric effect.

The next 30 years saw piezoelectricity reserved largely for laboratory experiments and further refinement. In World War I, piezoelectricity was used for practical applications in sonar. Sonar works by connecting a voltage to a piezoelectric transmitter. This is the inverse piezoelectric effect in action, which converts electrical energy into mechanical sound waves.

The sound waves travel through the water until they hit an object. They then return back to a source receiver. This receiver uses the direct piezoelectric effect to convert sound waves into an electrical voltage, which a signal-processing device can then process. Using the time between when the signal left and when it returned, an object’s distance can easily be calculated underwater.

With sonar a success, piezoelectricity gained the eager eyes of the military. World War II advanced the technology even further as researchers from the United States, Russia, and Japan worked to craft new man-made piezoelectric materials called ferroelectrics. This research led to two man-made materials used alongside natural quartz crystal, barium titanate, and lead zirconate titanate.

Piezoelectricity today

In today’s world of electronics, piezoelectricity is used everywhere. Asking Google for directions to a new restaurant uses piezoelectricity in the microphone. There’s even a subway in Tokyo that uses the power of human footsteps to power piezoelectric structures in the ground. You’ll also find piezoelectricity being used in these electronic applications:

Actuators

Actuators use piezoelectricity to power devices like knitting and braille machinery, video cameras, and smartphones. In this system, a metal plate and an actuator device sandwich together a piezoelectric material. Voltage is then applied to the piezoelectric material, which expands and contracts it. This movement causes the actuator to move as well.

Speakers & buzzers

Speakers use piezoelectricity to power devices like alarm clocks and other small mechanical devices that require high-quality audio capabilities. These systems take advantage of the inverse piezoelectric effect by converting an audio voltage signal into mechanical energy as sound waves.

Drivers

Drivers convert a low-voltage battery into a higher voltage which can then be used to drive a piezo device. This amplification process begins with an oscillator that outputs smaller sine waves. These sine waves are then amplified with a piezo amplifier.

Sensors

Sensors are used in various applications, such as microphones, amplified guitars, and medical imaging equipment. A piezoelectric microphone is used in these devices to detect pressure variations in sound waves, which can then be converted to an electrical signal for processing.

Power

One of the simplest applications for piezoelectricity is the electric cigarette lighter. Pressing the button of the lighter releases a spring-loaded hammer into a piezoelectric crystal. This produces an electrical current that crosses a spark gap to heat and ignite gas. This same piezoelectric power system is used in larger gas burners and oven ranges.

Motors

Piezoelectric crystals are perfect for applications that require precise accuracy, such as the movement of a motor. In these devices, the piezoelectric material receives an electric signal, which is then converted into mechanical energy to force a ceramic plate to move.

Piezoelectricity and the future

What does the future hold for piezoelectricity? The possibilities abound. One popular idea inventors are throwing around is using piezoelectricity for energy harvesting. Imagine having piezoelectric devices in your smartphone that could be activated from the simple movement of your body to keep them charged.

Thinking a bit bigger, you could also embed a piezoelectric system underneath highway pavement that the wheels of traveling cars can activate. This energy could then be used to light stoplights and other nearby devices. Couple that with a road filled with electric cars, and you’d find yourself in a net positive energy situation.

Want to help move piezoelectricity forward into the future? Get started with Fusion Electronics today.