As part of Autodesk’s annual Design & Make It Real program, the Make It Home affordable housing challenge invited students to reimagine how design and construction can strengthen communities through innovative, affordable housing solutions. The challenge is one of several initiatives within the program that encourage young people to apply design thinking to real-world problems in the built environment—while gaining early exposure to the tools and mindsets shaping today’s architecture, engineering, and construction industry.

This year, we’re sharing these stories during Construction Inclusion Week and Careers in Construction Month, a time to celebrate the diverse voices, perspectives, and pathways shaping the future of building. Each feature in this series pairs a student designer with an industry mentor whose insights illuminate how Design and Make skills and professional practice come together to drive meaningful change.

Today’s story brings together Fope Bademosi, Circular Economy and Construction Researcher at Autodesk, and Samuel Freeman Rathina Kumar, a rising sophomore at Ballantyne Ridge High School in Charlotte, North Carolina. His project, Project Senegal – Novel Approach to Housing, transforms personal experience into a powerful housing solution rooted in empathy, engineering, and global perspective.

Project Senegal addresses housing insecurity both abroad and at home—drawing inspiration from Samuel’s mission trip to Dakar, Senegal, where he met children living in unfinished concrete structures, and his volunteer work with unhoused families in Charlotte. Recognizing that housing is a human right, he set out to design modular homes that provide dignity, safety, and adaptability in extreme environments.

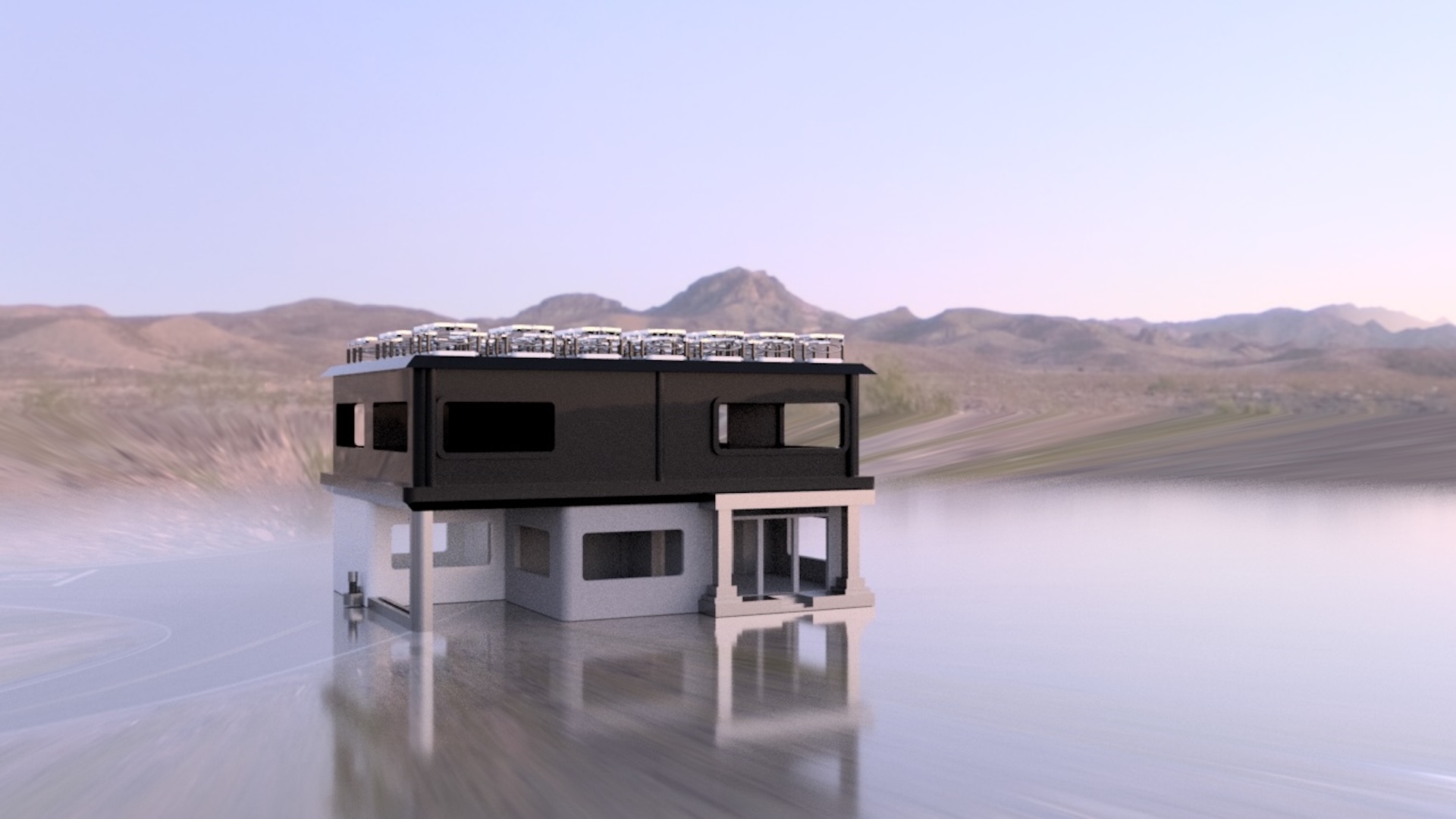

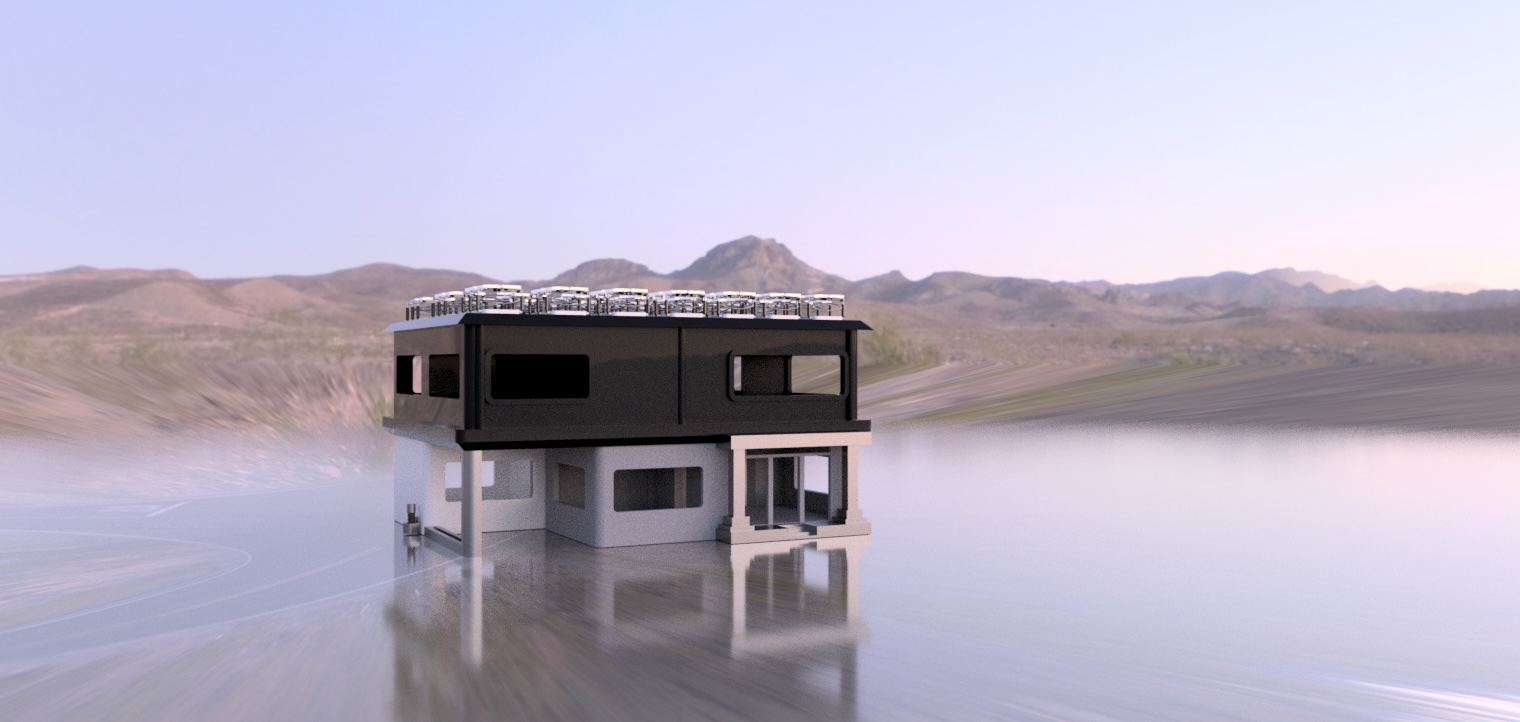

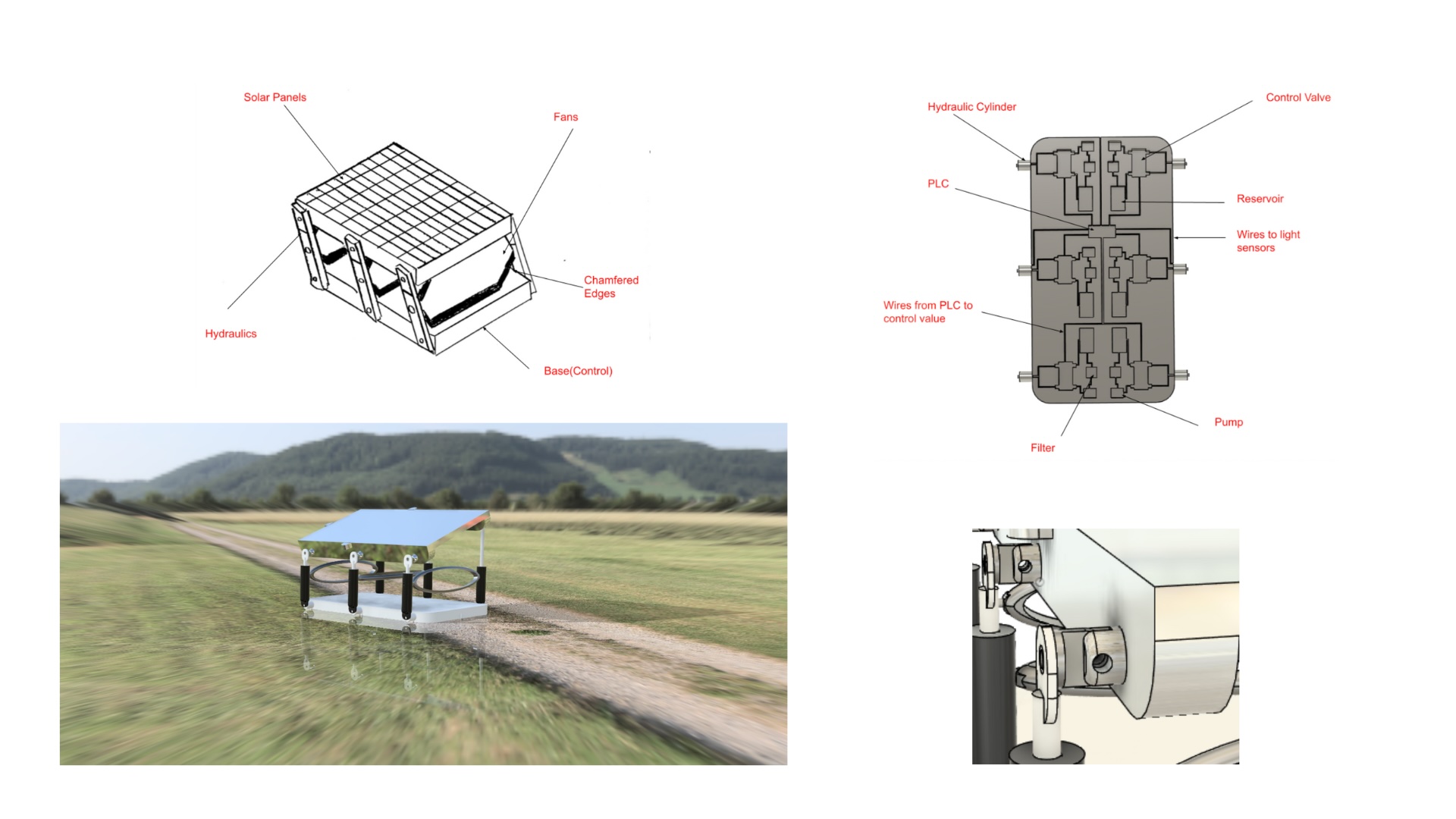

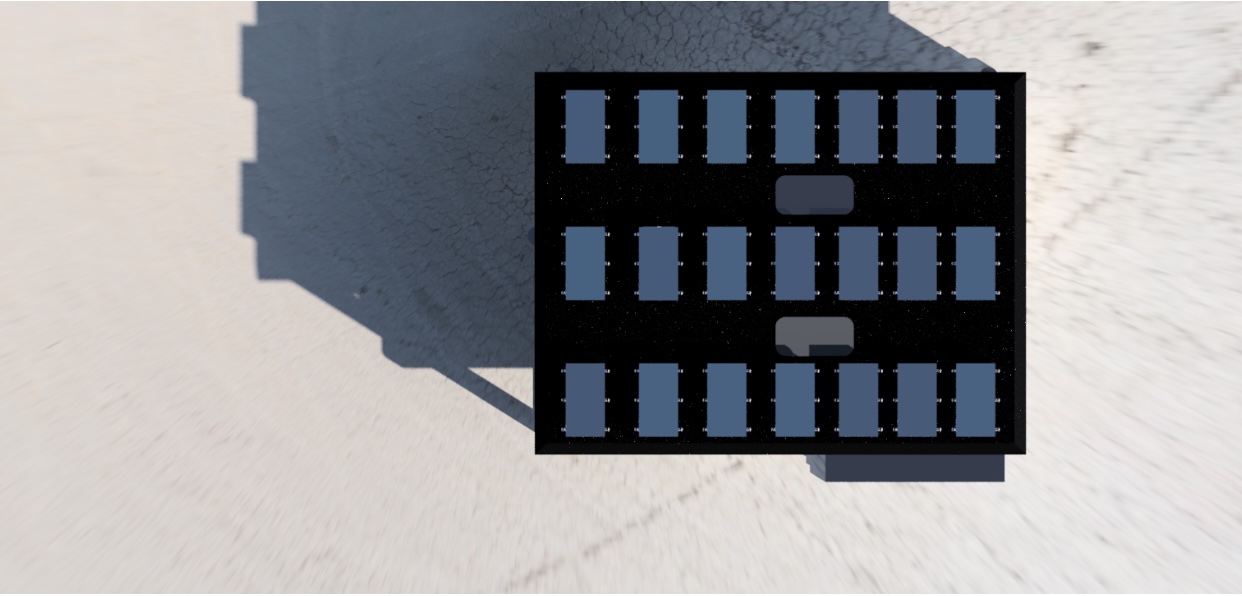

His solution combines three scalable housing modules with a hybrid solar/wind energy system (“Sunmill”) and a helical foundation system (“Soundation”) that anchors homes in sandy or clay soils. By integrating renewable energy, sustainable 3D-printed earth materials, and climate-responsive design, Samuel created a pathway for communities to build—and rebuild—with agency and resilience.

As a Circular Economy and Construction Researcher at Autodesk, Fope Bademosi specializes in sustainable construction, intelligent construction technologies, and net-zero strategies. With nearly a decade of experience across industry and academia, including teaching construction management at the Wentworth Institute of Technology, she is passionate about helping the next generation see construction as a force for change. She also leads educational outreach to empower students exploring careers in design and construction.

Project Senegal – Novel Approach to Housing

Student Designer: Samuel Freeman Rathina Kumar

Project Inspiration: Dakar, Senegal & Charlotte, North Carolina, USA

What immediately struck me about Samuel’s work was how he transformed deeply personal experiences into engineering solutions with genuine human impact. At just 15 years old, Samuel witnessed street children in Dakar, Senegal, who had been rejected by their families, and saw countless unfinished concrete houses with no roofs, exposed to rain and intense heat. Rather than simply feeling sympathy, he channeled these experiences into actionable design.

The technical sophistication is remarkable: the “Sunmill” hybrid solar/wind system with hydraulic tracking increases energy yield by 30-40%, and the “Soundation” helical foundation adapts to different soil types, from sand to clay. But what’s very impressive is how every technical decision serves a human purpose. The modular design isn’t just clever engineering; it directly addresses the reality that families often lack the financial resources to continue building, forcing them to stop construction and live in incomplete concrete shells.

His budget consciousness also stood out. Module 1 starts at just $18,000, and the complete three-module home costs $148,870, which could be made more affordable through grants and tax credits.

Coming from Nigeria, I’ve witnessed firsthand how housing inequality shapes entire communities. As a judge in the previous competitions, I was excited by the opportunity to observe once again how young minds tackle real-world challenges without the limitations of conventional thinking that often restrict professionals. These students aren’t constrained by “the way things have always been done.” They’re bringing fresh eyes to problems that affect billions globally.

What excites me most is the convergence of empathy and engineering I see across these projects. One project shows a high school graduate designing for Indigenous communities in northern Ontario, learning about their struggles with boil water advisories, inadequate healthcare, and unsafe housing filled with mold. Another student from Boston works in a Chinatown architecture firm and has designed vertical gardens that could lower temperatures by 10 degrees, addressing the neighborhood’s history of redlining and environmental injustice.

The global perspective is thrilling. From addressing homelessness in Seattle using recycled plastic, to creating affordable housing in Worcester, Massachusetts, to designing for Senegal’s sandy soils, these students understand that housing is a universal challenge requiring locally-adapted solutions.

The most inspiring aspect across all projects was the refusal to accept single-issue solutions. The Chinatown project explicitly states that “injustice is intersectional, and we must find solutions that are equally intersectional.” This philosophy was evident in many of the entries.

Students consistently demonstrated remarkable resourcefulness. The Daedalus Domes project would remove 240 tons of plastic from landfills per dome if printed from recycled materials, turning waste into shelter. Another project recognized that “yards make people happier, although this often isn’t available to working-class people” and put gardens on rooftops.

The level of technical sophistication was truly impressive. Many students taught themselves tools like Autodesk Fusion from scratch, created parametric designs, conducted soil testing, calculated heat transfer coefficients, and developed detailed budget analyses. One project incorporated HRV (Heat Recovery Ventilator) systems for moisture control in arctic conditions. These are pragmatic engineers in the making.

What particularly inspired me was their cultural sensitivity. One student researched that the Swampy Cree people traditionally lived in tipis with central hearths. They designed their modular core to emulate this gathering space, making it taller with clerestory windows to emphasize its importance. This level of cultural consideration from teenagers gives me tremendous hope.

I’m struck by how this generation refuses to compartmentalize problems. They see housing not as mere shelter, but as the intersection of climate change, social justice, mental health, cultural preservation, and economic opportunity. One student explicitly designed to combat depression through community spaces, noting that “knowing the people that live near you can help you become happier and even help with anxiety.”

The diversity of approaches — from 3D-printed domes to rammed earth construction, from floating houses to vertical gardens — shows these students aren’t looking for a one-size-fits-all solution.

They understand that Worcester needs different housing than Attawapiskat, that Boston’s Chinatown faces different challenges than rural Senegal.

For someone from Nigeria, where we face similar housing challenges, these projects demonstrate that solutions don’t need to come from wealthy nations or established institutions. They can come from a teenager with a 3D printer, a sketch pad, and the audacity to believe that everyone deserves a home they can be proud of.

These students aren’t just designing houses. They’re redesigning how we think about community, sustainability, and human dignity. If this is the next generation of architects, builders, and engineers, then I have tremendous hope for the future of affordable housing worldwide.

When he entered the Make It Home challenge, Samuel was a rising sophomore at Ballantyne Ridge High School in Charlotte, North Carolina. After witnessing poverty and unfinished housing in Senegal on a mission trip—and serving unhoused families in his own city—he felt compelled to design a solution rooted in empathy, innovation, and lived experience.

Project Senegal is derived from a complex world, viewed as a marginalized and inconspicuous community whose roots run deep in compassion, perseverance, and humility. Senegal, located in West Africa, is known for its gracious waves and its famous soccer player, “Mané,” but not so much for its everyday people. Our crew of five teenagers and three mentors landed in Senegal at 2 a.m., deprived of sleep and comfort from a 10-hour trip with delayed flights and missed terminals. We stayed at a host’s home where we took a well-needed nap that lasted five hours before we were awoken by the sound of an alarm. After we ate breakfast and did our devotions, our host took us to his mission home, where he helps underprivileged kids in Senegal who have been left on the streets or have run away from religious leaders who have hurt them.

Although we had done training at home, nothing could really ever prepare us to actually embrace another culture. When we finally met the children, we were blown away by their kindness toward us, outsiders that they had never even seen before. Then our host took us to play soccer with the kids, which completely blew me away again with how fast and agile they were compared to our crew. The entire experience was filled with laughs, kids calling me “Lamine Yamal,” and blood from our feet as they scratched the rocks in the sand. The experience helped us learn what it is to be content with what you have.

But on this 10-day trip, one thing really disrupted me. As we traveled along the highways, we saw unfinished concrete houses with no roofs, fully exposed to the rain and intense heat of Senegal. Steel pillars protruded from the tops of these structures, and the walls offered little protection, making them hardly feel like homes at all. These kids that we met on this trip had lived like this with no AC or fans. Determined to make a change not only in Senegal, but also for those in need closer to my own home in Charlotte, Project Senegal became a reality.

The inspiration for my housing solution directly came from the mission home that we visited in Senegal, where homeless children were sheltered and served. I chose a similarly situated area towards the outskirts of Dakar where poverty and homelessness are most evident. I realized I needed a site with naturally exposed sand to test. I identified a spot that my parents and I often visit during our hikes and walks in Charlotte. I chose the area near the Four Mile Creek that is sandy in soil type because that's also the soil type of Senegal. This helped me to research the problem as close to the real environment as possible, so that I could develop solutions that are suitable for the conditions that the communities of Senegal are in.

Project Senegal revealed to me that architects, engineers, and builders have a bigger role in the future beyond how society values them. Before I entered this competition, my initial views on AECO professionals were that they created buildings just for people according to their standards, whether that be for cost or practicality. But reflecting on this project, I realized that they have a much greater power in their hands—to solve issues like homelessness through their designs and ideas, creating masterful products that serve a real purpose in society. This project showed me that they can be compassionate human beings who can change the world around them through their work.

During Construction Inclusion Week and Careers in Construction Month, we celebrate stories like these—where mentorship meets imagination, and where the next generation of designers and builders are not just imagining a more inclusive future, but actively constructing it.

Stay tuned for more Student + Mentor Spotlights from Autodesk’s Design & Make It Real program, featuring inspiring conversations between professionals and students who are redefining what it means to design and make a better world. You can find previous stories here.