Tree-house architecture brings Modus Studio closer to nature

Modus Studio is using design and fabrication tools to bring people closer to nature; its tree-house architecture hews close to this mission.

Taz Khatri

October 1, 2021 • 6 min read

Modus Studio brought its expertise and technology to a tree-house architectural project in Arkansas.

Analyzing the tree canopy, the firm designed the Evans Tree House to be an immersive experience that incorporates the shapes of the forest around it.

Modus Studio uses an iterative process combining design and fabrication to bring projects to life.

When Modus Studio was invited to design the Evans Tree House at Garvan Woodland Gardens in Hot Springs, AR, its mission was to bring people closer to nature—or “biophilic design.” And what could better realize that mission than a dreamy tree house? Built in 2018 on a Ouachita Mountain hillside along Lake Hamilton, Evans is the first of three tree houses planned for the gardens to create an interactive educational experience that gets kids excited about the natural world.

Modus Studio is an architecture firm in Fayetteville, AR, with 29 people working in its design studio and fabrication shop. Modus often uses technology to understand how nature acts on building components, creating prototypes in the shop to test out in the elements. For Modus, technology isn’t the end-all; rather, it’s a tool used to achieve the highest design potential for each project. Many of the team members were raised in rural environments and maintain a strong connection to the area’s creeks and forests.

Bringing architectural practices to the woods

To integrate the Evans Tree House with the surrounding woods, the designers knew they couldn’t rely on conventional ways of documenting the site, such as a metric survey. The team opted for a laser scan, which produced a virtual 3D model of every tree and every branch in its precise location. With this detailed map at its disposal, Modus was able to carefully place the tree house where it would provide the most immersive experience.

“The easy thing to do would be to pick the clearest spot on the site and maximize the footprint as much as possible, but we didn’t think this would bring visitors close enough to nature,” says architect Jody Verser. He adds that Modus wanted to position the tree house “close to the trees so you’re walking up into the structure, and there’s this cadence and rhythm of wood fins, and you’re seeing trees pass by.”

How the tree canopy influenced the tree-house design

For the tree-house design, the laser scan led to the best solution. “The design drove where the tree house was going to be located, which is very close to the trees, curved between some of the trees,” Verser says. “To avoid conflicts, the site was scanned from 16 points so that we could build a point cloud and understand very clearly where the trees were and literally fit our model between those trees.” The tree house stands 13 feet off the ground (at its lowest point) on a steel structure.

Modus coined the term wood slug for the project, Verser says: “It’s made of wood and has this sluglike, tapering shape to it.” Designing this amorphous shape required an iterative process of writing custom Autodesk Dynamo scripts, hand sketching, 3D modeling, and collaborating within the entire design team.

Verser first developed the Dynamo script to describe the shapes of the cross-sections that later became wood fins. At that point, the team collaborated to refine those shapes. “The designers printed off some sections, and they sketched on those, scanned them, and they changed those lines—then, I sat down with them, and we ran through the Dynamo script again,” he says. This iterative process yielded the site-specific shape.

Modus took design cues from the science of dendrology (the study of trees), basing the design of the tree house’s metal screen on the way a leaf’s veins splay out from a central spine. “There’s a logic to how the screen is broken up, and most people should find it kind of familiar,” Verser says. “You could show that to someone, and it looks like a leaf—both from afar and when you zoom really, really far into a leaf.”

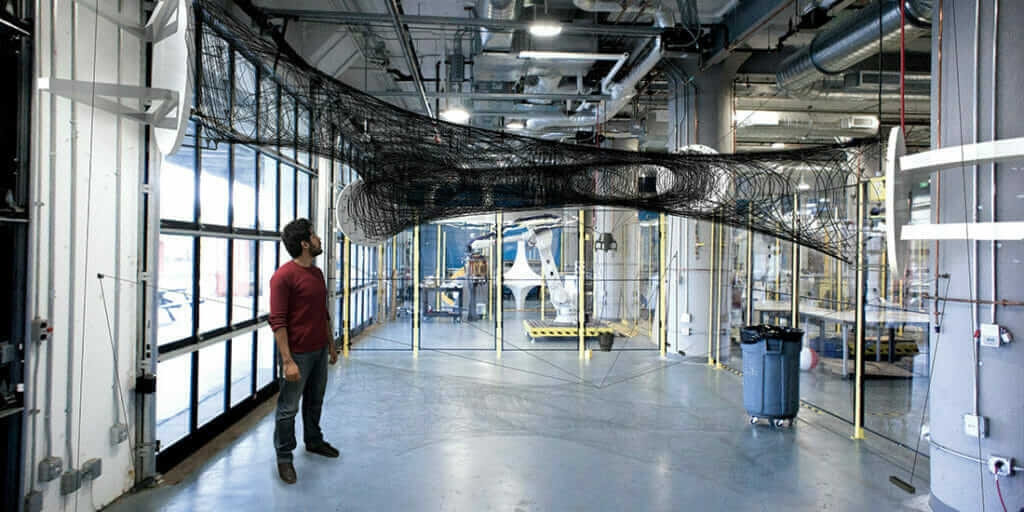

Fabrication to improve the design process

Modus’s fabrication shop is integral to how the firm designs: The guiding philosophy is that thinking and making should not be separate. Alongside technology, Modus sees fabrication as an indispensable tool to achieve the highest design potential for each project, iterating prototypes to improve designs. It creates an iterative feedback loop by combining laser scanning, computational design (with Dynamo), and fabrication (prototyping in the shop). By bringing the concepts of design and build together, Modus can design in 3D and then bring lessons from fabrication back into the design process. For example, Modus used the plasma cutter in its shop to test perforation patterns for the tree house’s metal screens.

“It’s like sketching but better,” Verser says. “But sort of amping that up a bit would be going out into the shop and building a full-scale mockup. You’re really starting to test it. And then you can throw it out in the sun; you can weather it; you can show it to the client. That’s always going to be more impactful than a 3D rendering.” Full-size mockups provide real-time indicators of how an element will work in the rain or in the sun.

While designing a different pavilion for Coler Mountain Bike Preserve’s South Gateway, Modus proposed a steel roof with a custom overlapping pattern—but first, the firm wanted to test how that roof would perform in the rain. “We built a mockup in the shop with some butyl tape and four plates of steel that we plasma-cut, then stuck it out in the rain for a while, poured some water on it in the shop, and saw how water came through,” Verser says. “We made some adjustments, then changed the detail and conveyed that to the contractor.” In this case, fabrication provided hard evidence of what worked and what didn’t.

Modus has applied these philosophies to projects such as Adohi Hall at the University of Arkansas, undertaken with two other architecture firms. “We had these frequent workshops with the client and would schedule meetings where we were all on the same call, looking at the same screen … and talk about how to fold it together and maintain cohesion,” Verser says. Although they divided the responsibilities, many decisions required close collaboration, using 3D modeling and real-time rendering to always visualize issues within the context of the whole project.

Modus also worked on an office project in Bentonville, AR, for a photography-based client, creating an interplay between form and function. “The concept of the chief facade took cues from a shutter opening, so there’s this bifurcation and folding of planes to create this shift in the building facade,” Verser says, adding that the shift drove the sequence of spaces and procession through the building.

Living inside a 3D world is not the same as living in the real world; Modus designs with one foot in each. It regularly opens its shop and studio to the public for lectures, workshops, and professional collaborations to share its vision with the community. Its unique iterative process bridges virtual and actual reality, producing highly site-specific design solutions that reach their fullest potential thanks to the firm’s own digital transformation.

This article has been updated. It originally published in February 2020.

About the author

Taz Khatri

Taz Khatri is a licensed architect and she has her own firm, Taz Khatri Studios. The firm specializes in small multifamily, historic preservation, and small commercial work. Taz is passionate about equity, urban design, and sustainability. She lives and works in Phoenix, AZ.