Generative design accelerates the BAC Mono street-legal race car into the future

The BAC Mono is a lean, mean, driving machine—literally. The one-seat, street-legal race car's superlight profile and generatively designed wheels lead to hyperacceleration and speed.

Zach Mortice

March 3, 2020 • 6 min read

The BAC Mono is a lightweight, street-legal supercar whose design used advanced technologies such as generative design and 3D printing to enhance performance.

Generative design helped reduce the weight of the wheels by 35%, optimizing their strength-to-weight ratio and aligning with BAC’s aesthetic and brand identity.

The car’s 332-horsepower engine propels it from 0 to 60 mph in just 2.6 seconds, with a top speed of 170 mph, thanks to its ultralight carbon-fiber chassis and other weight-saving measures.

BAC’s use of generative design and 3D printing allows for high customization and efficiency in small-scale production, paving the way for future innovations in automotive design and manufacturing.

What’s one of the most effective ways to make a car go faster? Slash its weight in half.

The BAC Mono is a stripped-down street-legal supercar that weighs a slight 570 kilograms (roughly 1,200 pounds), less than half of a Toyota Corolla. The interior is pared down to a single seat and has an ultralight carbon-fiber chassis. The car’s newest iteration—which was unveiled at the BAC Innovation Centre in Liverpool, England—sheds an additional 4.8 kilograms by using generatively designed wheels made with software that maximizes strength-to-weight ratios. Dropping that extra weight could spark a revolution in automotive design and manufacturing, dramatically altering the performance and appearance of cars.

Designed and built by Briggs Automotive Company (BAC) based in Liverpool, the BAC Mono is a lean race car that can also operate on city streets, meeting the legal minimum of pedestrian and safety protections. Its 4-cylinder, 2.3-liter turbocharged engine offers 332 horsepower, which doesn’t seem overwhelming, but the car’s lithe frame allows acceleration from 0 to 60 mph in only 2.6 seconds and a maximum speed of 170 mph. Car critics rave about the BAC Mono’s immediate acceleration and pickup, the apotheosis of go-kart–like agility and handling.

Each BAC Mono costs about $250,000. “Because we have a high price point and a low volume, we’re one of the first that can afford to absorb the costs of things that are more expensive,” says Ian Briggs, BAC co-founder and design director, who started the company with his brother Neill Briggs.

That means new fabrication methods, namely 3D printing. About 40 parts of the new BAC Mono are 3D-printed (headlights, wing mirrors, rear-light casings, and more), and many of the panels are made from graphene-enhanced carbon fiber, known for its low weight, strength, and thermal durability.

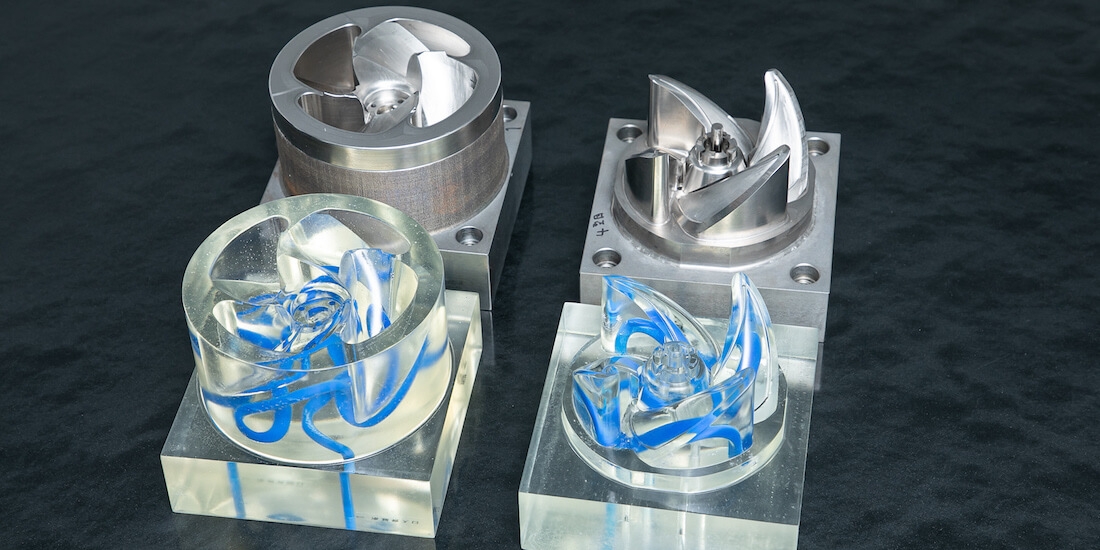

But most important for weight savings, BAC used generative-design technology in Autodesk Fusion 360 to produce the wheels. Generative design takes advantage of machine learning and cloud computing to design objects by algorithm; its final products can offer extreme strength-to-weight ratios. For the BAC Mono wheels, designers specified the required performance constraints (how much weight the wheels must bear), material used (aluminum), and the fabrication method (5-axis CNC milling to save cost). From those data points, the software generates nearly endless iterative options for the designers to choose and helps them explore a wider array of solutions, leading to much better results.

However, the design aesthetic was also a big constraint, as BAC wanted an evolution of the design that appears lightweight but also expresses its brand in the design. This meant the design was restricted in where it could place material, so it would conform to BAC’s desired aesthetic and brand identity.

Both 3D printing and generative design make customization easier, a key value for a small car company specializing in bespoke products. “As a small company, we prefer to save the investment into a tool that’s going to make thousands of components for another manufacturer when we’re only making 30, 40, 50 components a year,” Ian says. “That door opens easier for us than it does for mass manufacturers. 3D printing allows us to make just one. The seats are molded to the customer. The steering wheel is made for them, the pedals; everything’s unique. You could put their name and initials on the components. Our customers are buying a unique, high-price-point, special car. They fully expect to see the cutting edge of technology with things like generative design.”

Generative design and 3D printing reinforce each other, even if this feedback loop pushes fabrication to impractical places. In the most unlimited examples, the products of generative design resemble flesh and sinew; all assumed orthogonal geometry is gone. “If you let generative design do what it does and don’t give it any limitation, you end up with structures that could only be 3D printed,” Ian says. “As that price comes down, I think you’ll also see a bigger adoption of generative design and the types of solutions it comes up with.”

Making the new Mono’s wheels was like a small mass-production, so manufacturing with more established processes provided cost benefits. Therefore, BAC put constraints on the generative-design process to sidestep the expense of fabricating 3D-printed wheels, which could cost tens of thousands of dollars for a single set. Instead, the company set parameters so a 5-axis CNC mill can fabricate each wheel, which still offers more formal possibilities than previous versions of BAC Mono wheels, made with 3-axis machines. The new wheels are 35% lighter than standard wheels—tipping the scales at just 2.2 kilograms each.

The new wheels pare back and thin out both the spokes and the anchor point, elongating and smoothing the pentagonal spoke assembly into a seamless blend of rectilinear and curvilinear geometries. The circular coupler that connects to the axle shaft has additional holes drilled through it, creating a mildly biomorphic honeycomb texture.

While other car companies have experimented with generative design and topology optimization for wheels, the BAC Mono is a perfect aesthetic match for the biomorphic design language common to generative design. Riding low to the ground, it has the profile of a hammerhead shark or stingray—its sculpted, flowing chassis gives way to more exposed mechanical components toward the rear of the car. Generative design’s ligament logic fits better here than on a family sedan or crossover SUV.

The BAC Mono wheels don’t yet have the dynamic fluidity of the boldest examples of the technology, but as the wheel design coalesces around ultraefficient biological fiber patterns, the trajectory is clear. And once generative design does make it to auto showrooms and carpool lanes everywhere, the reduced weight and material economy that it unlocks can increase fuel efficiency, blunting cars’ impact on carbon emissions and climate change.

That’s a place BAC wants to go. Generative design holds the most promise for metal car components, and BAC sees suspension systems and chassis elements as the next steps in rendering its cars in biotic metal. “The wheels are phase one of a three- or four-phase approach for generative design in our future products,” says Neill, BAC co-founder and director of product development.

“We have 400 parts on the car that are machined from solid aluminum on a 3- or 5-axis milling machine,” Ian says. “Any one of those components could go into generative design and, for probably a very modest cost, be reduced in weight. We already mill them, so milling them a little bit longer with the advice of generative design would be the logical place for us to start saving weight. If there’s a chance to optimize the design, save weight, and still make it with the same process as before, it’s good value for the money and the weight savings. That seems entirely practical even today.”

About the author

Zach Mortice

Zach Mortice is an architectural journalist based in Chicago.