Minecraft architecture: What architects can learn from a video game

Minecraft has caught the attention of architects and designers. Can a game change how architecture is taught and practiced? See the amazing examples here.

Kim O’Connell

February 2, 2016 • 5 min read

The world-building video game Minecraft has garnered the attention of architects, designers, and animators who are using it in a wide range of projects and competitions.

As a computer-aided design (CAD) tool, the platform’s ease of use, emphasis on collaboration and community, and democratic approach to making architecture help users bridge the gaps between design and reality.

Minecraft architecture is also catching on as an educational tool, through summer camps, after-school education programs, and an officially sanctioned version of the game designed for classroom use and adaptability by teachers.

Since it burst onto the gaming scene in 2009, Minecraft has become one of the world’s most popular video games—so much so that Microsoft bought the game and its parent company for a whopping $2.5 billion in 2014.

Today, the world-building platform has also garnered the attention of architects and designers. Could a video game actually change the way architecture is taught and practiced?

For those who aren’t familiar with the architectural game (or who don’t have school-age children), Minecraft allows users to build houses, cities, underground bunkers, and whole virtual worlds using 3D textured cubes that represent different materials. The crude, cubist platform creates a pixelated landscape that looks like a rustic version of a LEGO set. In addition to their own free-form fantasy worlds, Minecraft users have replicated nearly every famous building in existence, including the Taj Mahal, the White House, and the Burj Khalifa.

Designers have taken notice of the phenomenon of Minecraft architecture. BlockWorks, for one, is a global team of architects, animators, and other designers using Minecraft in a wide range of projects within the realms of gaming, media, and education. Directed by James Delaney, currently an architecture student at Cambridge University in the UK, BlockWorks was launched in 2013 and now has 41 builders from more than 10 countries, ranging in age from 14 to 44.

“The team evolved from four of us playing creative Minecraft online as a game,” Delaney says. “We began to build on a larger scale and level of detail, and it soon became apparent Minecraft had potential as a serious design tool. We started working within the gaming industry and creating game maps and worlds for Minecraft players. As we began to take on work, we expanded the team to cater for this demand.”

To Delaney and his colleagues, Minecraft is actually a computer-aided design tool. He believes there is an ease with which people can begin building in this platform (counting kindergartners among its users). It helps that Minecraft designers operate from what Delaney calls its “human perspective,” building as they move through and inhabit a space.

The emphasis on and capability for real-time collaboration are also critical elements, Delaney says. Online sharing is a hallmark of the millennial generation and reminiscent of current architectural tools such as Building Information Modeling (BIM), which allows designers, clients, and end users to exchange performance information to a much finer degree than ever before.

In essence, Minecraft can encourage a more democratic, populist approach to making architecture. This is a concept that Danish architect Bjarke Ingels, founding principal of the firm BIG, asserted in his film Worldcraft, which was screened during the annual Future of StoryTelling summit in New York in 2014. “More than 100 million people populate Minecraft, where they can build their own worlds and inhabit them through play,” he says in the film. “These fictional worlds empower people with the tools to transform their own environments. This is what architecture ought to be.”

Minecraft’s sharing culture is vital for maintaining a healthy creative community, Delaney says. “This is one of our main reasons for taking great care over our own digital portfolio,” Delaney says. “The portfolio also serves the purpose of attracting new clients.”

Among other projects, BlockWorks’ portfolio includes a re-creation of classicist Andrea Palladio’s famous Villa Rotonda, built in association with the Royal Institution of British Architects (RIBA), along with background information on Palladian concepts and floor plans of other Palladian buildings, so that other Minecraft users can try similar constructs.

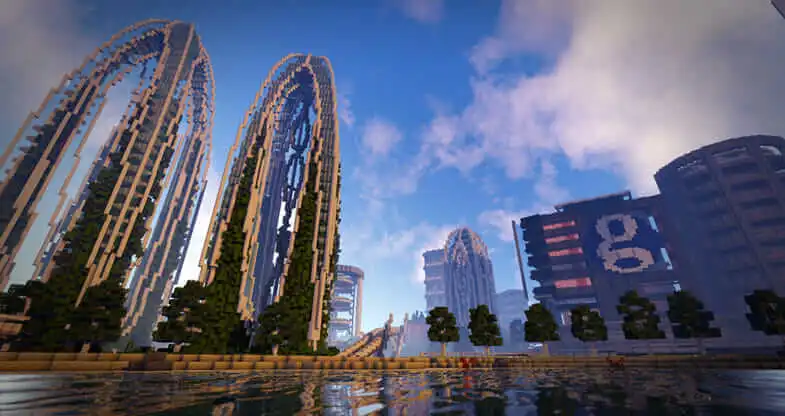

Another project, sponsored by the Guardian newspaper, asked the team to build a virtual city that used existing tools and technologies to create the most sustainable urban environment possible. This “city” is curving and organic, with wind farms and a structure based on London’s St. Paul’s Cathedral, whose classic dome is actually vegetated—a “biodome” that marries past, present, and future.

Last summer, for RIBA’s Day of Play event, BlockWorks set up a Brutalist Build workshop and competition, in which young players could bring their own laptops and connect to the RIBA Minecraft server, where they were assigned a plot and asked to create a Brutalist-inspired building. About 120 young people participated, ranging in age from 12 to mid-20s and representing 22 countries.

Minecraft and architecture are catching on as an educational tool elsewhere, too. The Chicago Architectural Foundation has offered Minecraft summer camps for students from age 7 through 18, and Zaniac, an after-school education center in Utah, has offered Minecraft architecture classes, as well. MinecraftEdu is an officially sanctioned version of the game that is specifically designed for classroom use and adaptability by teachers. Lesson plans cover everything from math and history to art; coding; and, yes, architecture.

“Whilst the architects of today grew up playing with LEGO, I have no doubt the next generation will have played Minecraft,” Delaney says. “People have to stop thinking of it as a game. It’s a CAD tool, and as such it is the most widely used one in the world. We’re looking forward to bridging the gaps between design and reality.”

About the author

Kim O’Connell

Kim O’Connell is a Washington, D.C.–area writer specializing in history, nature, architecture, and life. In addition to writing for a range of national and regional publications, she is a former writer in residence at the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts and Shenandoah National Park. She can be reached via her website, kimaoconnell.com.