Europe's urban centers provide visions of smarter, greener future cities

From Vienna and Paris to the small German town of Lemgo, discover the destinations now setting the agenda for smarter, greener future cities.

Carolin Werthmann

September 13, 2022 • 7 min read

Europe’s future cities will be greener, more digital, and completely inclusive.

Paris is already planning for the famous Champs-Élysées to become a green space.

Vienna, too, has long been regarded as a pioneering smart city focusing on gender planning.

Medium-size cities in Germany are also serving as models for the future.

To continue building cities of the future, it’s crucial to use digital tools.

Anne Hidalgo doesn’t like cars. She wants cars—and the exhaust fumes they produce—out of her city. Instead, she wants more trees, parks, and bicycle lanes. As the Socialist Party mayor of Paris, she is not alone in wanting to turn her city green. Many politicians are pursuing major changes in light of the EU’s goal of cutting greenhouse-gas emissions by at least 55% by 2030.

In recent years, Hidalgo developed multiple initiatives to nudge Paris a step closer in this direction. Under her direction, the city has built and upgraded bicycle lanes, planted trees, and inspired designs to transform the famous Champs-Élysées into a park. Hidalgo advocates a “15-minute city,” in which residents can reach schools, doctors, grocery stores, theaters, offices, and green spaces within 15 minutes of leaving their homes.

These initiatives mean Paris is a step closer to ending its smog problem. But smog isn’t the only issue in one of the most densely populated cities in the world. Rent prices are high, and affordable urban housing is a luxury. This dilemma is common to almost every metropolis in the world.

Future of cities’ vision: Less traffic, more space

Despite the 2020 global surge in remote working, the United Nations forecasts that 68% of the world’s population will be living in cities by 2050. As people continue to move to cities, the need for housing will grow—and traffic will get worse—as space becomes scarce.

Clearly, something needs to change. All over the world, designers are working on plans for the future of cities. For example, Japanese car manufacturer Toyota and Danish architecture firm BIG are planning the world’s first programmable city, dubbed Woven City, at the foot of Mount Fuji in Japan.

Meanwhile, the Saudi Arabian government wants to build NEOM, a roadless, car-free, entirely environmentally friendly city in the middle of the desert. A similar project is underway in the Chinese province of Hebei: The city of Xiong’an has been designed to help reduce overcrowding in the nearby capital of Beijing and is intended to become a kind of green Silicon Valley. Sidewalk Labs, a subsidiary of Alphabet Inc., had similar plans for Toronto, but the project is currently on hold.

Vienna as a model for the future of cities

Vienna is experimenting with future concepts, too. The city’s urban planners aim to take a range of perspectives into account when it comes to quality of life, using a technique called gender planning. Local town planner Eva Kail has been advocating for gender planning for more than 30 years.

“Most cities were essentially designed for men,” Kail says, explaining that streets, traffic routing, and living spaces are ultimately based on the antiquated model of a breadwinner who drives to work in the morning and comes back in the evening. “The immediate living environment has taken little account of the realities of life for those with domestic and child-rearing responsibilities.”

This is exactly what gender planning is changing. Streets that can easily be crossed with a stroller, as well as parks and daycare centers that can be reached on foot, are all part of the solution.

The results are clear: Vienna has ranked first on Mercer’s Quality of Living City Ranking for several years straight. It has also beaten London to top the Roland Berger Smart City Index.

“Vienna began looking at strategies for the future 10 years ago,” says Florian Woller, an expert at Smart City Agency. The agency is a department of Urban Innovation, a think tank that monitors and analyzes global trends and developments in metropolitan areas. “Back then, Vienna set a vision for where it wanted to be by 2030 and 2050,” Woller says. “The first framework strategy from 2014 has since been updated to set new criteria.”

Intelligent traffic lights and renewable energy

Vienna’s targets are ambitious: Per-capita carbon-dioxide emissions from the transport sector must be reduced by 50% by 2030 and by 100% by 2050; by 2050, 80% of components and materials from demolished buildings and major renovation projects must be reused or recycled.

It’s easy to make an agenda look good on paper. The real work is meeting the targets, and projects addressing electromobility, renewable energies from sewage sludge, temporary and shared use of spaces, and smart traffic lights are underway across Vienna.

Jochen Rabe, professor of urban resilience and digitalization at the Technische Universität Berlin, points out that pilot projects too often hope to bring about “new normalities” while failing to consider how those projects might be transferred to other areas or cities. He regards networking and exchanging ideas as critical for replicating projects after their test phase.

This kind of networking is the aim of the EU-funded Smarter Together, a joint project that aims to improve quality of life in transforming cities. The project is managed by Vienna; Munich; and Lyon, France, which have turned entire neighborhoods into test bubbles for new technologies and infrastructures. Sofia, Bulgaria; Venice, Italy; Santiago de Compostela, Spain; Kiev, Ukraine; and Yokohama, Japan, are involved as “successor” and “observer” cities.

Munich-based Smarter Together project manager Bernhard Klassen calls this structure a “snowball system” and defines the next step as finding new neighborhoods where solutions can be implemented.

Technology-driven urban planning for future of cities

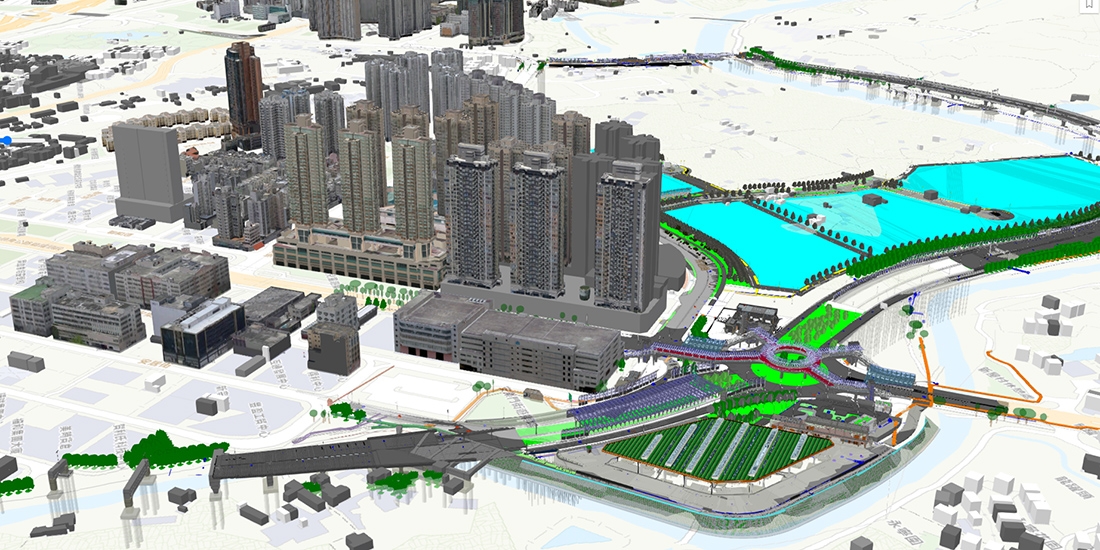

To achieve forward-thinking objectives, cities are relying on smart technologies that promise optimized infrastructure and logistics, as well as public and private spaces that are both livable and environmentally friendly.

The City of Oslo, Norway, used Autodesk Forma to plan one of its most important projects. Forma is based on artificial intelligence (AI) and uses generative design to calculate the optimum development for a plot of land. It takes into account parameters such as wind, solar radiation, clearance, noise, and daylight to improve housing standards.

In Oslo, this architectural reevaluation and design helped reduce low-light residential areas by 51% and noisy residential areas by 10%. With Forma, the planners were able to plan sustainably and saved several days of laborious manual work by using AI expertise.

“In the early stages—so during the planning and design phases—you can have a major impact on sustainability,” says Autodesk Senior Director Håvard Haukeland. “The cost of change during these stages is much lower than it is during retrofitting in later stages, such as construction and operation.”

Future cities don’t have to be big

There are many reasons why big cities are beacons and showcases. Metropolitan areas are home to major companies. They are business locations and magnets for science and research. They are where the networks driving new developments are concentrated. But small and medium-size cities have also long been focuses of interest. The German towns of Ulm, Kaiserslautern, and Gera were among 13 model projects in the Smart Cities dialog platform, which was initiated by the German Federal Ministry of the Interior, Building, and Community in 2019.

Climate-neutral neighborhoods will be built in the southwestern German town of Kaiserslautern, on a former factory site owned by sewing-machine manufacturer Georg Michael Pfaff. The Fraunhofer Institute for Solar Energy Systems (ISE) is providing scientific support for the project, called Enstadt: Pfaff Reallabor.

In the town of Lemgo, in northwestern Germany, researchers took a similar approach to experiment with creating a medium-size city of the future, in cooperation with the Fraunhofer Institute of Optronics, System Technologies, and Image Exploitation (IOSB). “It’s all about turning the structural disadvantage of a small town into an advantage,” says Jürgen Jasperneite, professor of computer networks at the Ostwestfalen-Lippe University of Applied Sciences and Arts and head of the Fraunhofer IOSB.

The project sees small municipalities as offering alternatives to and providing relief for big cities instead of remaining suspended in time. This focus on revitalizing smaller cities is similar to those being rolled out by Munich, Lyon, and Vienna as part of the Smarter Together initiative.

When the mayor of Paris advocates a “15-minute city,” she means self-sufficient neighborhoods that essentially function like villages and small towns. In the end, all projects serve the same purpose, whether they are realized in small communities, metropolises, or megacities. That purpose is to ensure that knowledge is networked, and solutions are globally adaptable.

This article has been updated. It originally published July 2021.

About the author

Carolin Werthmann

Carolin Werthmann studied literature, art, and media science at the University of Konstanz and has worked for Callwey Verlag, a German publisher specializing in architecture, crafts and landscape architecture. She also studied Cultural Journalism at University of Television and Film in Munich (HFF Munich) and currently writes for publications including the Süddeutsche Zeitung, one of Germany’s leading newspapers.