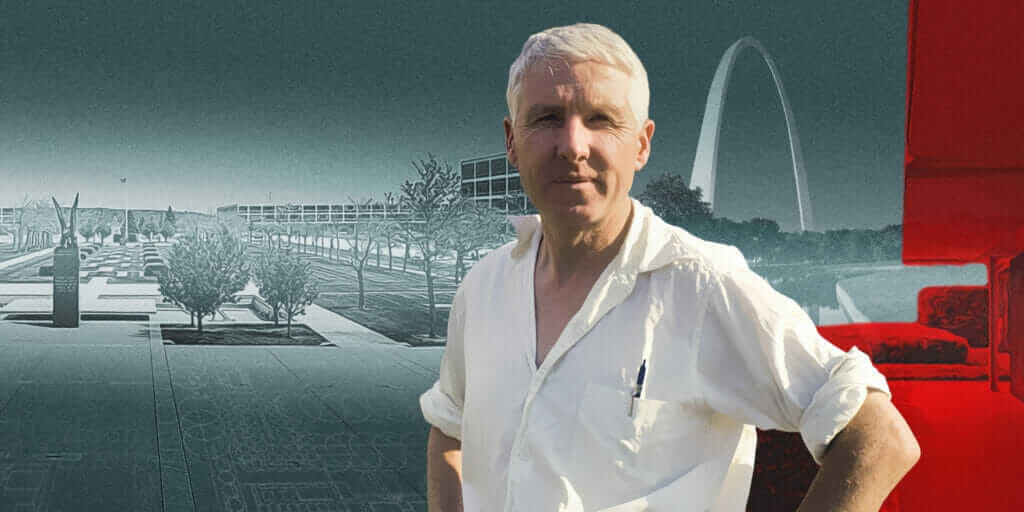

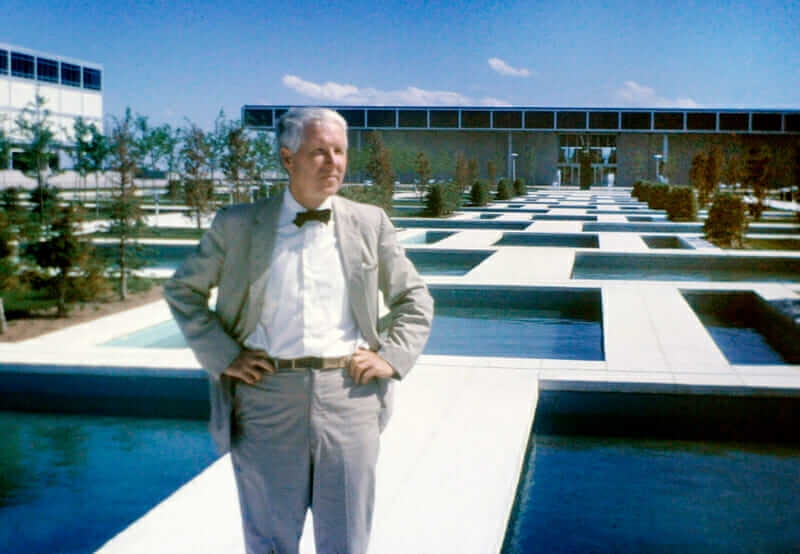

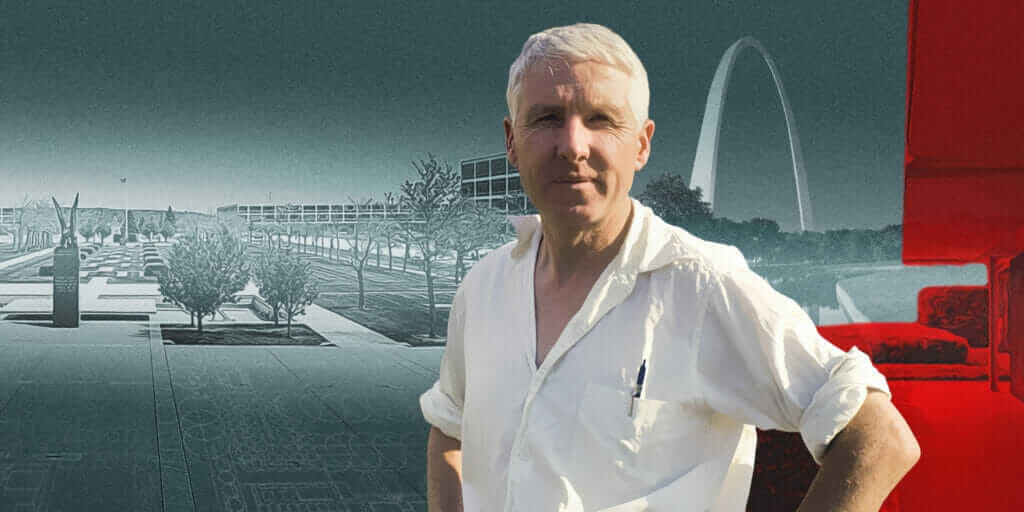

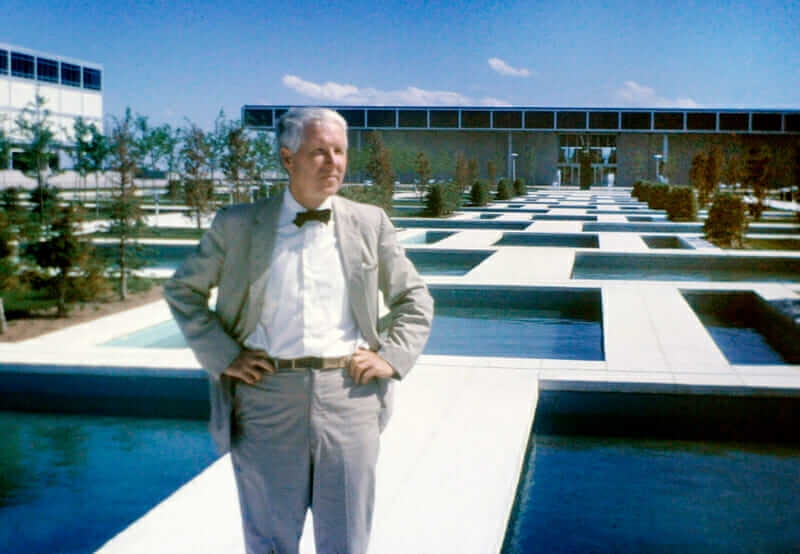

Local content only: dan-kiley

Subhead Placeholder

Rich Text Placeholder

Rich Text Placeholder

Rich Text Placeholder

Rich Text Placeholder

Rich Text Placeholder

Rich Text Placeholder

About the author

Kim O'Connell

Bio Placeholder

Subhead Placeholder

Rich Text Placeholder

Rich Text Placeholder

Rich Text Placeholder

Rich Text Placeholder

Rich Text Placeholder

Rich Text Placeholder

Bio Placeholder