From 3D printing to apps, 4 ways students are fighting coronavirus worldwide

Students are helping those in need during the coronavirus pandemic by 3D printing face shields and programming apps that monitor disease progression.

Carolin Werthmann

May 21, 2020 • 4 min read

Student projects from around the world highlight the power of technology to fight the coronavirus—3D printing PPE and app development as a particular focus.

Collaborations between students, educators, and industry partners fostered innovation and facilitated rapid production of creative solutions.

These student projects showcase the transformative potential of technology in empowering the next generation of innovators to tackle real-world problems and drive positive change.

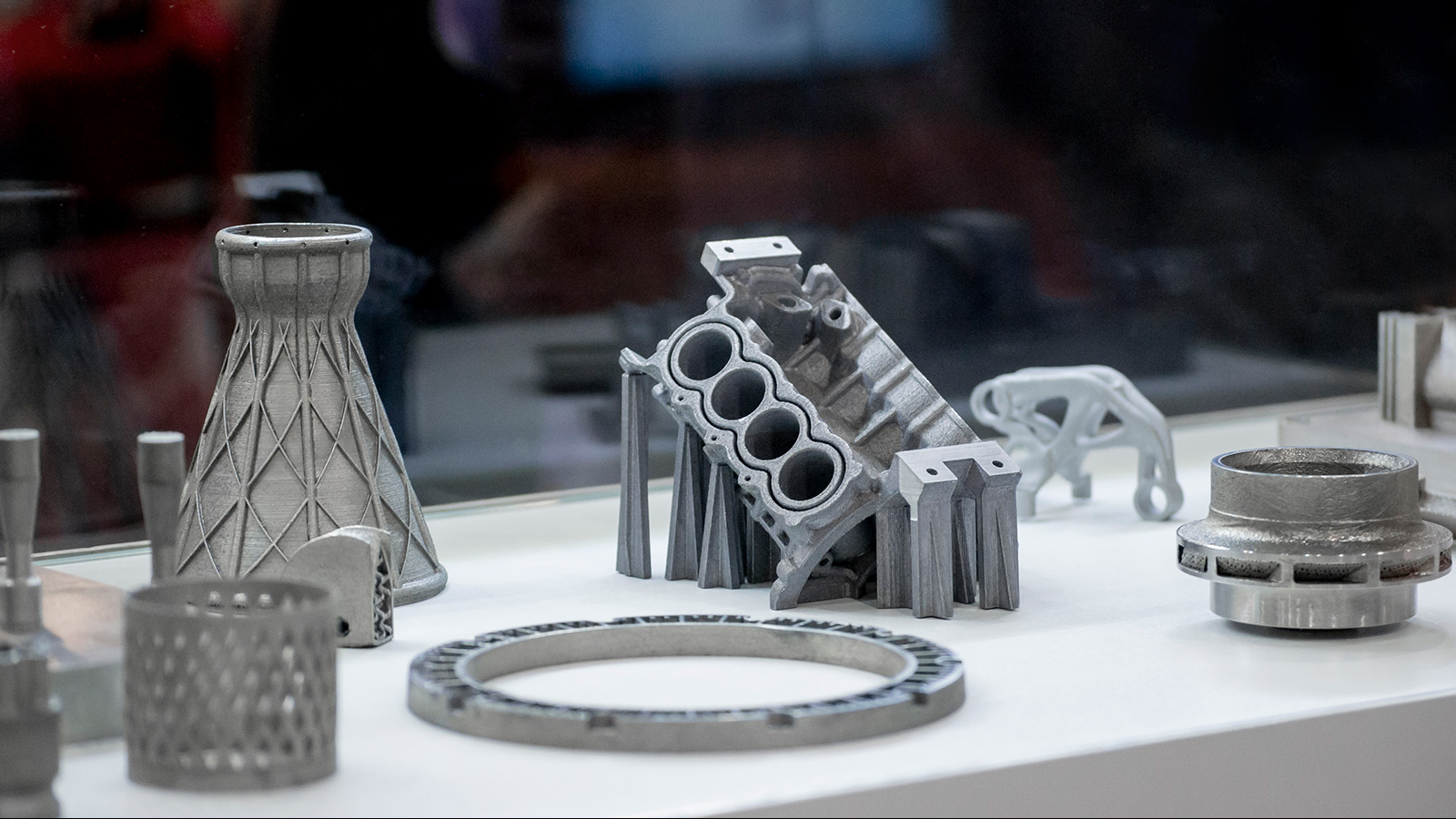

1. 3D-printing personal protective equipment (PPE)

One of the many important challenges government health agencies have faced in recent weeks has involved obtaining enough PPE. With stocks often dwindling or depleted, medical and emergency professionals in constant close contact with COVID-19 patients are at increased risk of becoming infected. But a partnership among Dresden Technical University (TU Dresden); DRESDEN-Concept, an alliance of research institutions; and biosaxony, a medical and biotechnology association, is helping to reduce this shortage. Researchers on the project use 3D printing and injection molding to manufacture plastic visors, 3,000 of which have been delivered to hospitals, fire departments, and doctor’s offices.

3D Printing Media Network, an open-source platform, provides researchers with the CAD documents required for producing the visors. Doctoral candidates and staff at the University Hospital of TU Dresden and biosaxony then conduct quality assessments, disinfect the shields, and prepare them for distribution.

“The face shields we received are very important to our daily emergency services,” says Michael Klahre, spokesman for the Dresden Fire Department. “They offer effective protection against potential infection, particularly when intubating patients who need to be placed on a ventilator before arriving at a hospital and when swabbing the nose, mouth, and throat.”

2. Producing Face Shields for the NHS

Elizabeth Bishop, a postgraduate researcher and specialist in additive manufacturing at the University of Warwick in England, is working on a similar project. With her team of engineering students, she uses large-scale fused deposition modeling and 3D printing to produce face shields for the UK’s National Health Service. Bishop and her colleagues can now print a headband and visor in less than four minutes.

Created in Autodesk Fusion 360, the face shield design can be used with any size of printer nozzle.

Bishop points out, however, that the face shields she makes do not have the CE marking, which certifies conformity with protection standards in the EU. “They should therefore only be used as a secondary protective layer or in emergencies where no CE-certified shields are available,” she says.

3. Making masks more comfortable

Italian start-up Isinnova has already been using 3D printing to adapt scuba masks from French sporting goods manufacturer Decathlon for medical use in Italy. However, traditional diving masks fit snuggly on a person’s head and are meant to be airtight, so wearing one for several hours can cause headaches, and complaints of a lack of oxygen are common.

Now, Stanford University is organizing a competition for students from around the world, looking to see who can best improve the scuba-mask design for a better fit. The new design should be both comfortable and reusable, while at the same time complying with the standards of an N95 or FFP2 respirator mask. There’s no need for a snorkel; instead, a filter must be attached to the masks. This then catches droplets that could transmit viruses such as SARS-CoV-2.

4. Hacking toward app-based prevention

At the end of March, the German government organized a hackathon under the hashtag #WirvsVirus. The aim was to generate a wide range of online solutions in the fight against the novel coronavirus. The event was open to anyone interested in submitting their ideas, and participants were asked to create a team that had 48 hours to design or prototype an app.

The 28,361 participants in the hackathon included 15 students and aspiring engineers from the Association of German Engineers (VDI). Siemens research engineer Andreas Stutz and research assistant at RWTH Aachen University Torben Deppe led a team of software developers, scientists, and engineers to create an app called Deeper, which allows users to monitor the progression of the disease and learn whether they have been in an area with an increased risk of infection.

The app combines features from the Corona Data Donation app developed by the Robert Koch Institute, the CovApp produced by the Charité hospital in Berlin (which also gathers information on users’ symptoms and generates advice for them to follow), and a contact-tracing app. Because the technology already existed, the Deeper team has decided to make its probability-based algorithm available to other developers on an open-source platform.

About the author

Carolin Werthmann

Carolin Werthmann studied literature, art, and media science at the University of Konstanz and has worked for Callwey Verlag, a German publisher specializing in architecture, crafts and landscape architecture. She also studied Cultural Journalism at University of Television and Film in Munich (HFF Munich) and currently writes for publications including the Süddeutsche Zeitung, one of Germany’s leading newspapers.